|

|

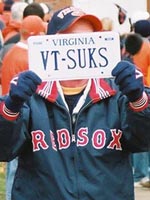

Receiver Ahmad Hawkins poses after scoring on a 46-yard pass play to win over Virginia Tech in 1998. It was the greatest comeback in the history of Virginia football. |

If you’re afraid they might discover your redneck past,

There are a hundred ways to cover your redneck past,

They’ll never send you home. – “Your Redneck Past” by Ben Folds Five

Some University of Virginia fans feel like Virginia Tech has been trying to cover its redneck past for years.

Perhaps it first started when the unwieldy former name of the school, Virginia Agricultural and Mechanical College and Polytechnic Institute, was shortened by dropping the “Agricultural and Mechanical College” in 1896. Virginia Polytechnic Institute, or VPI, was further rebranded to the sleeker, more gentrified Virginia Tech.

And the mascot since the early 1900’s, the Fighting Gobblers, not the most aristocratic of birds, was changed to the ambiguous Hokies in the late 1970’s and early 80’s, because, according to the official school website, one of their coaches “didn’t like the image” and “even removed the gobble from the scoreboard – current football coach Frank Beamer had it reinstalled.” Benjamin Franklin once promoted the turkey as our national bird, but that was not enough to save it from disuse by Virginia Tech, who in 1982 changed the Gobbler mascot’s costume to one that looked like “a maroon cardinal with a snood” and started referring to it as “The Hokie Bird.”

And whether it’s an intentional cover-up, or just lost details over the passage of time, one event in the football feud between the schools has become a little hazy – but it’s the reason why the animosity all began.

It’s one thing to dislike a rival, but when fans (and players) start using the word “hate” you wonder how it got this bad. Why do these two programs dislike each other so much? It’s as if the two factions have been trained to vilify the other, but don’t know why. It’s like the many examples of school traditions that have been passed down for generations that are continued by present day participants, who do not know the inspiration of their actions.

Fans may wonder about the curious outburst from the announcer at Scott Stadium who yells: “And that’s another Cavalier …” while the crowd completes the sentence with: “FIRST DOWN!” This chant first started with fans decades ago, but why are we cheering so much for a first down? Is it because we had little else to cheer for in the 1960’s until the George Welsh era? Or was it to rile up the opposing team? In either case, we do it because … everyone else does.

In a society sometimes obsessed with marking anniversaries of every kind, it’s interesting to take a look back 100 years in history. In 1911 Ronald Reagan was born, the Mona Lisa was stolen from the Louvre, Roald Amundsen led the first expedition to reach the South Pole, and the University of Virginia and Virginia Polytechnic Institute did not play a football game.

That last part seems odd. First, because the football rivalry between UVa and Virginia Tech does not usually connote “historic significance” – except for some UVa and Virginia Tech fans – but also because these teams played every year, right?

In a rivalry that began in 1895, that has accounted for 92 games, why is there is a 17-season gap in this series in the early 20th century? Except for a two-season hiatus during WWII, and a three-year blip in the late sixties, these teams have played almost every other campaign except for the period from 1906-1922.

By now, many die-hard fans on both sides of the rivalry may have heard the story of Virginia Tech’s Hunter Carpenter. A fantastic account of his exploits was chronicled in the book Hoos ‘n’ Hokies: The Rivalry, by Roland Lazenby and Doug Doughty. Even USA Today within the past decade has commented on Carpenter’s contentious past. So while this is not a shocking, long-forgotten story that is just now being retold, let’s dig a bit deeper – on both sides – as UVa doesn’t get away without its own issues to contend with.

As the story goes, Virginia Tech’s Hunter Carpenter enrolled at Tech in 1898 as a 15 year old, played varsity football from 1899-1903 and did not taste victory over powerhouse UVa during that stretch, so he transferred to UNC where he was quoted as saying “I just want to beat the University of Virginia.” Carpenter lost yet again. But with a never-say-die attitude he returned to Virginia Tech in 1905 for one last shot at UVa, and was the star of the game as Tech finally beat its nemesis.

Sounds great, right? A true David-versus-Goliath story. If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again? The 2004 Virginia Tech Magazine summarized the aftermath by writing “U.Va. was so incensed by the loss that it refused to play Tech again until 1923.” Well there you have it. UVa was a poor loser who took its ball and went home. But wait. If one peels back the layers, it’s a bit more complicated than that. And it’s the subtleties in this story that are the reason this rivalry has been so contentious, or as some fans are saying, hateful, almost from the beginning.

|

|

The rivalry gets heated at times on both sides. |

Almost. And that’s because, believe it or not, University of Virginia football alumni helped build the Virginia Tech football team from scratch. Yes, just as UVa’s former President John Casteen came to the rescue to save the Hokies from a soon-to-be crumbling Big East Conference when he brokered the deal that helped usher Virginia Tech into the ACC in 2003, it was blue-blooded, Virginia gentlemen who trained some of the very first VPI footballers.

Looking back into the archives of Virginia Tech, the school’s 1903 yearbook, The Bugle, published an article on the then 11-year history of football at VPI. “When the fall of 1892 opened, Professor W.E. Anderson, who had played on the team at the University of Virginia … (and others) took counsel together, with the result that a team was organized … with Professor Anderson as captain.” A professor as captain? Eligibility rules at that time were obviously loose.

Without “competent training” it was written, the team did not fare well. Foretelling the future fanaticism of Hokie followers, the article stated “If as much encouragement is given to our teams in the future as discouragement has been in the past, we predict that defeat will be as uncommon as was victory this year.”

After two years and a 1-3 combined record, the VPI football committee “appealed to Mr. Joseph A. Massie, now a graduate from the University of Virginia, to come to the help of his old Alma Mater and train our team for us.” Massie had an interesting path as he attended VPI in 1891, migrated to UVa where he ultimately graduated after playing football from 1892-1893, and then returned to Blacksburg the next year as the head coach (and we assume attended some graduate classes) while also playing quarterback. Massie lead Tech to a 4-1 record.

|

|

Lambeth Field and Grandstands |

In the next two seasons another UVa graduate, Arlie “A.C.” Jones, coached the VPI team with the assistance of a former Virginia quarterback, Taylor Saunders, and additional support from Massie. Hokie fans may not like the sound of that, but a cadre of three UVa alums – one who admittedly attended both schools – was in charge of Virginia Tech football for their initial brush with success as the team went 13-5-1 in those three seasons and became football crazy. As The Bugle bluntly put it: “Football had come to stay.”

Relations between the schools were pleasant enough for a while. UVa had alpha dog status as the first football team in the South – one that would not have a losing record in its first 28 seasons – and demolished Virginia Tech 175-5 combined in their first eight contests. But tension was brewing more than ever with one Hokie footballer, Hunter Carpenter.

In the fall of 1901, Carpenter’s senior year according to The Bugle, where his large picture and honors were displayed along with other fourth-year students, Virginia traveled to Blacksburg for the first time in the rivalry’s history, and won 16-0 on the gridiron that was first carved by a plow into a football field 10 years earlier.

Carpenter graduated the Spring after the 1901 campaign, when he won All-South honors. But, having played only three seasons of football, he subsequently entered a graduate program at VPI in 1902, and became the team captain. This time the Hokies and fifth-year senior Hunter Carpenter lost at Lambeth Field by an oh-so-slim 6-0 margin, on a touchdown even UVa later agreed should have been disallowed. His unattainable goal, Carpenter’s white whale, was ever so close, but swimming away. Check Meijer Ad and Walgreens Ad.

This apparently did not sit well with him.

Four seasons played in five years of school. That sounds normal today, and it was an unofficial standard for many universities and colleges at that time. Occasionally a fifth year was not frowned-upon by opponents. That held true at Virginia, whose records indicate one lone instance where a player enjoyed a fifth year of competition in 1895. Virginia Tech’s media guide however, despite the ease in which the names and dates could be obtained from yearbooks and other records, omits listing any lettermen in football prior to the 1932 season.

Pushing the boundaries of the loose rules of the day, in 1903 Hunter Carpenter then entered his sixth year at VPI and would start his fifth on the varsity football team. He was officially listed as a member of the faculty with the role of “Assistant in Surveying.” Whether or not this position came with a salary has not been documented. But if it was, with Carpenter continuing to play football, the line between amateur and professional was becoming very blurry. In a triumphant campaign, Carpenter led Tech to a 5-1 record with their only blemish coming yet again at the hands of the University of Virginia, 21-0.

Also on that team was C.P. “Sally” Miles, the future Tech coach and Athletic Director for many years. Miles played but four seasons at Tech, and remained to coach the “2nd Team” the year after his graduation. Interestingly, while Miles could have followed suit with his teammate and played a fifth year, he did not.

|

|

The rivalry dates back to the 1800’s. |

If the story ended here, not much would have been made of it, and the UVa/VT rivalry may not have turned so nasty. But it didn’t end. Lazenby, of the afore-mentioned Hoos ‘n’ Hokies: The Rivalry, says Carpenter “burned to beat Virginia.” The Captain Ahab of college football set sail for North Carolina where he entered law school and joined the UNC football program for the 1904 campaign and his sixth year as footballer. Carolina had gone 6-3 the prior season with a 16-0 victory over UVa, so Carpenter felt he had a good chance to put this winless streak against Virginia to rest.

In a bitter twist of fate, in the closing moments of the Thanksgiving Day game between UVa and UNC in Richmond, Virginia tied the score and was attempting an extra point to win. The kick was low! And it would never have made it over the crossbar, until it ricocheted off a Carolina player and limped through the goalposts. Carpenter lost yet again. Moby Dick had taken Ahab’s leg.

Officials at the University of Virginia were becoming increasingly agitated. After seeing Carpenter on the field for five successive seasons while at Tech, they had faced him for a sixth while he was at UNC. That same season, an athlete began the year with Penn State and played so well against powerhouse rival Penn that he was convinced to transfer to the Quakers overnight. Two weeks later he competed for Penn in a 24-0 drubbing of UVa. Penn went 12-0 on the season capturing a share of the National Championship, fueled in part by “tramp” athletes. Virginia was not pleased.

Losing to teams with no regards for eligibility had to stop. UVa’s new President, Edwin Alderman, launched a committee to research and recommend eligibility standards in the hopes it would level the playing field for all schools.

Carpenter, meanwhile, was crushed. He had boasted to reporters that his sole goal was to beat the University of Virginia. Coincidentally, earlier in the season, the Hokies had competed in a tight game with UVa losing only 5-0. Carpenter’s mind started to race. He couldn’t, could he? Another season at Tech? Unlike the tramp athletes that never attended classes, and were not even listed on rosters, Carpenter was a star who appeared in many newspaper reports. He had been awarded All-South honors. Everyone knew of his exploits.

The media frenzy started even before the 1905 season began. College Topics, the precursor to UVa’s Cavalier Daily, and The Daily Progress both began questioning Carpenter’s eligibility. Was a seventh season of football allowed? Was he getting paid by the school? Or by boosters? Scholarship money, or even remuneration for room and board, was strictly forbidden. The Bugle this time did not list Carpenter as a faculty member. Instead he was enrolled as a graduate student.

College Topics claimed it had proof that Carpenter was being paid to play. The Virginia Tech student paper pointed fingers at UVa officials for slandering an innocent man’s name. The game was called off, and then it was back on. Retractions were made by The Daily Progress. UVa officials tried to cancel the game for good, but Virginia Tech’s team showed up at Lambeth Field anyway.

Going into the interstate rivalry game, Tech had blown away its previous competition. It beat traditional power Army at West Point. It crushed UNC 35-6. In fact, Tech would only be scored upon twice that entire 9-1 season. On top of it all, Tech was desperate to put an end to its futility against the Wahoos.

Virginia on the other hand was reeling.

A new student on Grounds, former Columbia captain Tom Thorp, had just enrolled at Virginia after failing out of the New York school. His first appearance at Lambeth Field for practice with the “scrub eleven” attracted a large crowd that cheered as if it were a game. Virginia thought it had a star on its hands. But while happy to give Thorp a second chance to earn a Virginia degree, President Alderman insisted he could not join the football team for one year, to prove that he was not brought in solely for his athletic prowess.

Adding injuries to insult, three UVa starters endured broken collarbones derailing a promising team that was 4-1 going into the game with Virginia Tech, the only loss to the Carlisle Indian School. What was left of this patchwork assembly of players resorted to playing soccer during practice to avoid further casualties and put out a call to any able-bodied student who wanted to join the program.

In the week before the game, the entire Virginia student body met at Madison Hall and took a vote on whether to play the game. It was decided that UVa would play, but afterward would end all future athletic relations with Virginia Tech after the game. The consensus was UVa would still come out victorious, and it did not want to disappoint fans by not playing the contest.

|

|

Even friends take sides in the UVa-VT rivalry each year. |

As the teams were warming up at Lambeth Field, the students who ran the athletic department at UVa left the crude wooden bleachers that lined the hillside (Lambeth Stadium and the Colonnades were still eight years away) and prevented the Virginia Tech team from taking the field. They presented Carpenter with an affidavit to sign, denying he was a “professional.” Again Carpenter protested his innocence.

Additionally, a new wrinkle had arisen, drawing into further question whether Carpenter was eligible. The Virginia Intercollegiate Athletic Association, one of the smaller sub-conferences of which VPI was a member, banned the playing of postgraduate players. UVa officials felt there was no way Virginia Tech could refute this. But in a bit of twisted logic, Carpenter and his teammates argued that since UVa had withdrawn from the conference that February (which was true), it could not enforce these rules. Virginia’s student officials, without the authority to disqualify Carpenter, reluctantly agreed to allow play with the Hokies’ star player in the lineup.

Carpenter started off the scoring with a long touchdown run and the ragtag bunch of Wahoos could not keep pace. Newspaper accounts told of punches thrown both at and by Carpenter. During a long run the VPI hero received another blow by a defender, and was tossed from the game after delivering a powerful retort of his own. Indignantly he threw the ball into the stands with the officials escorting him from the game and the crowd roaring in delight. Fans thought this was their chance. But in a second half that lasted 65 minutes, and only ended due to darkness, the Hokies prevailed 11-0.

The Virginia Tech fans rejoiced. Newspapers across the state proclaimed the underdog had finally had his day. Hunter Carpenter finally achieved his ultimate goal. And the career-college student, who had played Hokie baseball every spring after his losses to UVa in football each fall, decided he had enough with college, and hung up his hat and glove instead of finishing out his eighth year of college like the others.

His football coach that year, former teammate “Sally” Miles, would not forget this episode either, as he continued his distaste for the Cavaliers as Tech’s Athletic Director and in other roles until 1956.

While UVa licked its wounds, it also went on to its most successful era in history. Over the next 10 seasons Virginia would average seven wins and only 1.6 losses, including its only undefeated season. The Cavaliers also held true to their vow to sever football ties with VPI. And they would continue to do so for the next 17 seasons.

In looking at The Bugle once again after that 1905 season we can see why. In the previous eight issues after a loss to UVa, there was nary a word of discussion on the topic. But this year, the victors relished their spoils and then some. Calling their vanquished foes an “Aggregation by reputation shady” and devoting three pages to photos of fireworks on the VPI campus after the win, a cartoon of a beaten bulldog (representing UVa) along with the score 11-0, and worst of all, a caricature of UVa athletics director William Lambeth preaching “Pure Athletics” to the public, while holding out a $100 bill to a football player behind him.

|

|

“The Bugle” at Virginia Tech published this caricature of William Lambeth. |

In addition, a fictional story in The Bugle, which was common in yearbooks at the time, surmised that “the colleges that are the crookedest … are the first to holler ‘crooks’ … when they get beat by another team … but the charmer of them all, for playing crooks and accusing others, be that University of Virginia … everyone knows athletics at the University are as crooked as a fence rail. Dr. Lambeth … goes around the country picking out his team from the colleges where they’ve been playing for twenty years.”

This went beyond winning and losing. Virginia Tech had offended the honor of the University. Not only had VPI perpetrated a fraud in the minds of UVa officials, it then had the audacity to imply improprieties by Virginia’s esteemed “Father of Athletics.” UVa felt justified in its policing of Hunter Carpenter’s eligibility by the sheer fact that his mere presence on the team alone was against the rules. But VPI had no evidence to back up its implications of wrongdoing by William Lambeth. It would take a 17-season hiatus before Lambeth could be convinced to put Virginia Tech back on the schedule.

Over the years Virginia would continue to be criticized for its eagerness to point the finger at others. It would go on to cancel contests between Georgetown and UNC due to allegations of “ringers” on those squads. But Alderman’s committee on eligibility, two months after the Hunter Carpenter incident, established eligibility guidelines that would later be used throughout college football. And UVa’s insistence on playing only teams that followed those same guidelines helped usher in an era of stringent uniform standards.

Interestingly, Carpenter was not mentioned at all in The Bugle after Virginia Tech’s victory that season. But a century after that game the Winter 2008 issue of Virginia Tech Magazine trumpeted him as a hero, while downplaying the somewhat unbelievable length of his tenure as a football player. It states: “The incomparable VPI football legend Hunter Carpenter played … five years – yes, that’s five – on the team … starring as VPI’s halfback from 1899-1903 … and for his final season in 1905.” Somehow the author confuses the fact that this would be six seasons as a Hokie footballer, emphasizes how crazy even five seasons would be, and fails to tally his seventh season for his time at UNC.

When UVa and Virginia Tech fans engage in their spirited rivalry this Saturday, many will find levity in the situation and enjoy the spectacle that is college football. But others will let their emotions take over and may truly feel a sense of hate. They won’t be the first, and they won’t be the last, and many will not even know why. 106 years has still not quelled that sensation entirely. And it all started with one player, who didn’t want to leave.

About The Author: Kevin Edds is the Writer/Director of the documentary Wahoowa: The History of Virginia Cavalier Football. For more information on the film, please visit www.UVaFootballHistory.com. TheSabre.com periodically features articles on the history of UVa football where Edds, an alumnus, highlights some of the most interesting moments in the more than 120-year history of the South’s oldest football program. Email Kevin here.

Wahoowa: The History of Virginia Cavalier Football |

|

|

|