About The Author: Kevin Edds is the Writer/Director of the documentary Wahoowa: The History of Virginia Cavalier Football. You can purchase the DVD from our sponsor UVA Bookstores (click here). For more information on the film, please visit www.UVaFootballHistory.com. TheSabre.com periodically features articles on the history of UVa athletics where Edds, an alumnus, highlights some of the most interesting moments and people in the history of Virginia sports. Email Kevin here.

A Tar Heel in Cavalier country doesn’t find himself easily acclimated to the ways of a Virginia Gentleman. As the son of a Major in the Confederate Army growing up during the difficult Reconstruction Era, William Lambeth arrived at UVa to study medicine in 1890. There were no dormitories, no First Year Facebooks, no ice-breaker mixers to help integrate him into the culture of the University. Yet when he found himself drawn to the burgeoning athletics program at UVa, not only did he carve out a niche for himself in Charlottesville, he ultimately would revolutionize the way we play sports, not only at the University but across the country.

When Lambeth came to UVa, sports had just begun to take off. Many students of the 1870s and early 1880s were the sons of Civil War veterans; athletics were the least of their concerns. However, as football continued its meteoric rise in popularity in the Northeastern colleges, Virginia soon caught wind of the excitement and began its own program in 1887.

When Lambeth first strolled the Grounds, games were played in a dirt field, which is now the site of the Scott Stadium East Parking Lot or in the gravel-strewn plot behind Madison Hall in what came to be known as Mad Bowl. (Read more about the history of Virginia’s football fields in this article from the EDGE archives.)

|

|

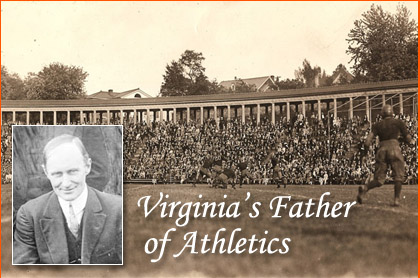

1913 Washington Post photo of Dr. Lambeth. |

UVa’s football team, called the Virginians or sometimes the Rebels, was starting its fourth year of collegiate competition when Lambeth arrived. After playing nearby boarding school Pantops Academy in 1887 followed by a series of meetings with some small-time football programs like those from Johns Hopkins, Georgetown, and Wake Forest in the following two years, Virginia scheduled an ambitious lineup in 1890. The season opened with a made-for-newspapers double-header weekend featuring UVa – the “Power of the South” – against the reigning National Champion Princeton Tigers as well as a Pennsylvania Quakers team that would eventually go 11-3 that year.

After suffering a 72-0 defeat to Penn in Washington, DC, UVa’s “eleven” were shellacked 115-0 just 24 hours later by Princeton at Oriole Park in Baltimore. Virginia’s players realized they needed to polish up their game before resuming any series with the best programs of the Northeast.

Despite the losses, William Lambeth was hooked. Football had indeed arrived in the South. During Lambeth’s tenure as a student at UVa, the team would lose only once in its next nine games, establishing itself as an upstart program South of the Mason Dixon Line. After receiving his medical degree in 1892, Lambeth was hired by the University to run the daily operations of the new Fayerweather Gymnasium, the finest indoor athletic facility of its time in the South, as he continued to work on his Ph.D. But he did more than run a gym.

As an employed alumnus with an interest in athletics, Lambeth was able to volunteer to help the various sports teams at the University organize their operations. Newspaper reports in the following years described Lambeth as the “Athletic Director” as far back as 1892. Student to AD in less than a year? That’s quite the leap.

The position of “Athletics Director” actually did not yet exist in the South. Scheduling games, making roster decisions, and managing everything from players to equipment to the facilities were tasks typically within the domain of an ad hoc committee of students and professors. Find the Offers This Week and Lidl Offers in it every day to save more. In fact, one of the most important responsibilities of a modern athletics director was not even made official until Lambeth picked up the mantle in 1892: the hiring of coaches.

From 1887-91, the UVa football team had no coach. The players merely elected a Captain and a team President, as the club was run like any other extracurricular organization at a University. But in 1891 the student newspaper, College Topics, a publication whose inception was borne out of the desire to publicize Virginia’s athletic teams, declared: “Everyone recognizes that the greatest need of the football team at the present is some one to coach the men.”

So in Lambeth’s first year as AD, he hired the first football coach in UVa history: William Spicer, a halfback from the very Princeton team that had decimated the Wahoos in 1890. Spicer led the UVa team to a relatively successful 3-2-1 record his first season. But the following year Lambeth hired another former Princeton player, John Penton Poe, a relative of former UVa student and poet, Edgar Allan Poe. The results were immediate as Poe guided the Virginia squad to an 8-3 season in 1893, winning its last five games by a combined score of 138-0.

In the fall of 1894, Virginia won with shutouts in its first two games to achieve a seven-game winning streak. The next game was a rematch with Poe’s alma mater Princeton, back in Baltimore, only four years after the 115-point embarrassment. This time Lambeth and the Virginia contingent scheduled a wise nine-day break before the contest. Under Poe’s direction, Virginia showcased its rapid ascent in the college football world as it played the Tigers tough in a 12-0 loss. With Princeton winning one of the several unofficial National Championship awards that year, Virginia’s boys had something to build on.

Next UVa faced its other opponent from that double-header weekend in 1890, the Penn Quakers. Losing in a similar heart-breaking fashion to Penn, 14-6, Virginia was one of only three teams to even score on the 12-0 Quakers that season, who shared the co-National Championship with Princeton that same year. In only four years, Virginia accomplished a dramatic turnaround from its first encounters with the football elite. All with William Lambeth overseeing the program. Virginia’s success would continue for years as it did not experience a losing campaign from its inaugural season in 1887 until almost 30 years later in 1916.

After helping the UVa football program gain its footing, Lambeth headed to Harvard where he not only received a degree from its School of Physical Training in 1895, but also witnessed the Crimson football team’s 33-4 record over three seasons. As part of the elite “Big Four” – alongside Princeton, Penn, and Yale – the Crimson of Harvard were college football royalty, drawing big crowds, big money, and big media attention. The allure of football at its highest stature gripped Lambeth and inspired him to bring that program ethic to Virginia.

Returning to UVa, Lambeth became an instructor in physical education, joined the medical faculty, and reclaimed his role as Athletics Director. By 1899 he was also writing articles for Outing magazine, an “Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Recreation” considered by some to be the Sports Illustrated of its day. His series entitled “Football in the South” gave updates to the progress of Southern programs like Virginia, UNC, Trinity (later known as Duke), Sewanee, Georgia, Vanderbilt, Alabama, and others. This no doubt gave a spotlight to not only Virginia football, but to the author who was also running that program.

Lambeth’s quest to build a big-time college football program also meant having the facilities commensurate with such a status. Finding a site not far from Jefferson’s Rotunda, Lambeth would build one of the greatest memorials to the birth of American Football. Work began in 1901 on 21-acre “Lambeth Field,” which had previously been part of the Rugby Dairy Farm. When it opened in 1902, it was home to many UVa sports, including baseball and track. Fans were encouraged to attend the games in wagons or horse-and-buggies so as to get a better view of the action. Eventually a crude wooden grandstand was built with a covered section for special guests of the University.

On the field, Virginia’s football team was not only a Southern juggernaut, but was becoming one of the best in the nation. While AP rankings did not come into existence until 1936, many of UVa’s teams during this era would have undoubtedly finished in the top five in the country. From 1908-1915 the Virginia football squad ended seasons with only one loss four times and also achieved its only undefeated season in 1908 (a 0-0 tie with Sewanee ruined a perfect record that year). In fact, that season the Virginia team gave up only 9 points combined, and those came in a 18-9 victory against St. John’s.

While a devout football man and prominent professor, Lambeth’s interests expanded beyond sports and medicine. He was a botanist and a geologist; he traveled to Italy in a quest to help develop the teaching of Italian at the University and later received the Order of the Crown of Italy for his efforts. He published books on environmental science and architecture, including 1911’s “Thomas Jefferson, Architect”; his research undoubtedly impacted his decision to upgrade Lambeth Field.

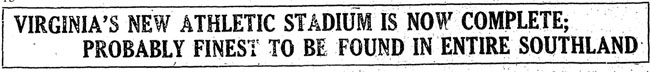

Over the next two years, the wooden bleachers that had been erected after the initial opening were demolished, and a more classical stadium with an impressive 8,000-seat capacity went under construction. Lambeth Stadium, the Colonnades, and the surrounding areas were completed in 1913 for close to $50,000 with money raised by Lambeth and alumni. The Washington Post called it, “the finest athletic outfit at any education institution in the South.”

With all of the success and growth of the sports programs and facilities at Virginia, Lambeth became known by a new moniker amongst the students: The Father of Athletics at the University. While not an official title, it was endearing nonetheless. But not only was Lambeth helping to build a well-rounded and successful athletic department, he was involved in the development of sports nationwide.

Lambeth had served as the vice president of physical education at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, where the UVa baseball team finished second to Yale in an intercollegiate competition. He was a member of the American Olympic Committee for the 1908 Games in Stockholm, a three-time President of the Virginia Intercollegiate Association (a mini-athletic conference of the era), and the Treasurer of the NCAA. He was a leader in establishing intercollegiate track rules and regulations, helped create eligibility guidelines that were later adopted by the NCAA, and was one of the driving forces in the creation of the Southern Conference whose members included most of the modern-day SEC and ACC teams.

|

|

Archer Christian at Woodberry Forest in 1909. |

But perhaps his most important contribution to sports took place a few years prior to the completion of Lambeth Stadium and helped cement Lambeth’s role as a leader in college football – that truly American game. As Sally Jenkins described in The Real All-Americans, “The Game, like the country in which is was invented, was a rough, bastardized thing that jumped out of the mud.” Football had, almost literally, sprung from the muddy soccer and rugby fields on American college campuses. But the game was far more dangerous than its predecessors, as Lambeth and the University of Virginia would find out.

In a 1909 contest with Georgetown, UVa football player Archer Christian was trampled under a mass of players suffering severe head injuries that would result in his death. This was not an isolated case. Football’s violent ways had led to dozens of deaths in the sport each year and the toll was rising.

The tragedy made the front page of the New York Times with an editorial pleading for the game to be abolished. Talk of outlawing football surfaced in the Virginia State Assembly. University of Virginia President Edwin Alderman, an admitted fan of football, embarked on a public crusade to reform the rules of the sport. Alderman had earlier told the press, “I love football and believe in it and am not afraid to get up in public and say so. When played in the right way it is a noble game. It gives a man that courage and grit which can be obtained probably in no other line of sport.”

But the Inter-Collegiate Athletic Association – later to become the NCAA – was only four years old, and was susceptible to the political power of the football elite which preferred the status quo with the game’s rules as their teams were doing quite well with them. With his favorite sport in danger of being abolished, Alderman traveled to New York along with Lambeth. Here Alderman made an appeal before the ICAA.

Alderman pleaded with the rules committee to consider revisions that would make the game less violent. Archer Christian was not alone. Eight other young men already had died playing college ball around the country that year. They needed to change the rules. Six schools, most notably West Virginia, already had decided to abolish the game.

|

|

Walter Camp in 1876. |

Alderman’s speeches before the ICAA were masterpieces. “He combined the moral with the practical, the carrot of hope with the stick of abandonment” says John Watterson, author of College Football. History. Spectacle. Controversy. Alderman’s solution was not to ban football, but to change it.

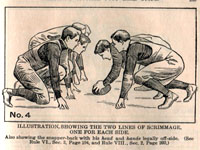

Coincidentally, the year prior to Christian’s death, William Lambeth had been invited to join the ICAA’s football rules committee. Now Alderman would have an ally on the inside. Opposing Lambeth though would be Walter Camp, the de facto leader of the rules group, someone who preferred the old ways of college football. While Lambeth was known as The Father of Athletics at UVA, Camp was resoundingly hailed as “The Father of American Football.” Camp was the one who invented the idea of a line of scrimmage, as opposed to the “scrum” early football had co-opted from rugby, and devised its scoring system. Changing the game as drastically as Alderman and Lambeth wanted would be a challenge.

Instead of striking an adversarial tone with Camp, Lambeth chose the opposite tact. Upon returning to Charlottesville, he wrote a letter to Camp that read:

“I am anxious, as I know you are, to eliminate all danger as far as possible from football. The two deaths I have seen in the game were due to exhaustion by the long continued effort without opportunity to recuperate defensive strength …

In a struggle of 35 minutes, the 35th minute is the most dangerous one as I see it … Could not the game be divided into four quarters …?

This would give a game of sixty minutes actual play, two halves of thirty minutes play … and each half divided into two quarters of 15 minutes.

One case of death I saw myself. Just before the end of the last half the fullback was injured and staggering half unconsciously into three plays before his teammates could be informed of his condition. He was led to the side line and died that night, never having regained consciousness.

I am sending enquiries concerning the deaths of others, so that I may have further information on this point.”

Lambeth, who witnessed Christian’s fatal accident, was also at the University in 1895 when George Phelan, a law student, died during a football game between “the Laws and the Meds.” He was there too in 1897 when a University of Georgia player was killed during a game against Virginia in Athens.

|

|

1909 Rule Book (above. Photo courtesy Alumni Association: UVa vs Georgetown Alumni Association game in 1909. |

|

Being so close to the Archer Christian tragedy inspired Lambeth like few others on the committee. These were his boys dying on the field playing a sport he had the ability to change for the better. In another coincidence, not only was Lambeth an alumnus of Virginia, but he received his graduate degree from Harvard, so he could potentially bridge the philosophical gap between the Big Four football schools and the smaller programs of college football.

Additionally, he was no doubt a student of the game. Lambeth’s New York Times obituary stated that he “devised many successful plays, the best known of which was the wide sweep from punt formation.”

Here was Lambeth, who had a foot in both worlds. A UVa man, and a Harvard man. A doctor, and a strategist. An administrator who had seen his students die on the football field, and yet a fan that still loved the game. A more perfect representative on the rules committee could not have been found.

Perhaps being a doctor led Lambeth to view the game from its physical nature in a way that was different. Rail thin, Lambeth did not have the stature necessary to play the game himself, so he was aware more than most of the dangers. Lambeth already required all potential UVa athletes to be examined and pass a series of physical tests prior to joining any athletic teams.

The rules by which the game were played at this time made it more of a contest of endurance and brute, physical force. Strategy and agility were a much smaller component. Player substitution restrictions were very much like present-day World Cup Soccer – once a player was substituted for, he could not return to the game. So, with teams wanting to keep their best players on the field until the final gun, many experienced exhaustion.

Also like soccer, American football was played in two halves. As games went on, offenses would begin to direct their attacks toward the weakest players on the defense. Exhaustion led to slow reactions and ultimately to dangerous injuries.

One way to give the players more rest, Lambeth thought, was to divide the game into four quarters, with a “breathing spell” between the periods and a long break at halftime. Opponents of this rule thought that it ruined the flow of the game. Imagine a modern-day World Cup soccer match that had three long breaks during the competition in addition to time outs. Purists would be up in arms. Football’s most loyal followers thought Lambeth was insane.

Surprisingly, Lambeth received a letter from Camp which, according to the New York Times, “asked Lambeth to get the Virginia varsity eleven and substitutes to try out his suggestions in actual scrimmages.”

The proposed new rules stated that, after substitutions, players could return to the game. Seven men would be required on the line during the snap (preventing “mass momentum plays”), players could no longer push-and-pull the ball carrier, and the forward pass could now be made across the line of scrimmage. Under Lambeth’s watch, on the Grounds of the University at Lambeth Stadium, a new version of American football, divided into four quarters, was played for the first time in history.

While putting football on a path that led to a safer game, Lambeth had also helped create parity between teams across the country. Like the 3-point shot in basketball, football’s new “four-quarters rule” – and the lessened restrictions on the forward pass – opened up the possibility of smaller teams defeating the Goliath’s of the football world. This rule would ultimately be used throughout college, high school, and ultimately professional football. And the parity it brought about had no small part in increasing the excitement for football at colleges everywhere. Now the little guys had a chance to compete with the Harvard, Princeton, and Yale teams.

Looking back on the 1910 season that took place under the new rules, Lambeth complimented his fellow committee members for “preserving to the youth of America one of the most powerful and useful auxilery [sic] forces in the educational system.” The sport that had intrigued Lambeth as a first-year man at Virginia had become one of his life’s passions. It held value to him. But like Jefferson continuously tinkering with the design of Monticello until his final days, Lambeth tweaked and modified the very structure of football, remaining on the NCAA rules committee for years to follow.

The game of football in 1909 – that had led to so many deaths – was still holding on to the vestiges of soccer and rugby that birthed it. Yet one year later, on the field that still lies in the cradle of Lambeth Stadium, America saw its first glimpse of the version of the game we now know today, overseen by the “Father of Athletics” at the University of Virginia.

Note from the author: Please consider a small donation to the William Lambeth Memorial Plaque Fund. The UVa Board of Visitors unanimously approved the creation and installation of a memorial plaque made of Buckingham slate to be installed at Lambeth Stadium at the Colonnades, but not the finances to cover it. The Edds family provided funds in advance to cover the not inexpensive production of this long-overdue memorial, but would greatly appreciate your help. A small donation by you, the fans of TheSabre.com, will help complete this project and allow you to be a part of this historical event. Thank you! Click here to donate.