|

|

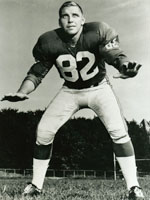

Tom Scott in 1952. |

This Saturday when Michael Rocco first steps under center for the Cavaliers during the UVa spring football game, imagine his reaction if he saw 6’5″ 245-pound Chris Slade lining up on the other side of the line of scrimmage, wearing his New England Patriots helmet. And what if on the other end he saw 6’3″ 270-pound Chris Long of the St. Louis Rams digging his cleats in, while in a three-point stance, wearing his St. Louis Rams helmet ready to barrel down on Rocco?

That is similar to the scene that former UVa quarterback Gene Arnette (Class of 1968) encountered during his time playing “varsity football” at UVa. His was an era when UVa alumni with NFL pedigrees would return to Charlottesville for the “Varsity-Alumni Spring Football Game,” a relic of bygone days in college football. During these contests, instead of playing an intra-squad scrimmage like the one that takes place now in the spring, UVa’s “Varsity” members competed against recent, and old-school, alumni.

“I can remember when I was coming up my junior year and senior year,” Arnette remembers, “going ‘Whew! I’ve seen this alumni game and I don’t know if I want a whole lot of this action.'” That “action,” included both College and NFL Hall of Famers returning to UVa to compete and wreak havoc on their fellow Wahoos.

“Tom Scott, number 82, when you saw him over there, you didn’t want any part of him. You didn’t care how old he was,” Arnette vividly recalls. Scott was a college All-American at UVa, competing from 1949-52, and like Slade, he terrorized opposing NFL quarterbacks too during his 12-year career with the Philadelphia Eagles and the New York Giants. “He always came back,” said Arnette. “He was the most loyal alumnus.”

The Early Years

While it sounds like an incredible marketing ploy today, the game was born out of necessity in the spring of 1953.

“We didn’t have a lot of scholarships back then so we didn’t have enough to scrimmage,” said Harrison “Chief” Nesbit (Class of ’51), an assistant football coach at UVa from 1951-58. “Ned McDonald [the UVa head coach at the time] said if we could get back a few guys that graduated we could get a game.”

Along with former UVa captain Robert “Rock” Weir ” (Class of ’51), who organized things from the alumni side, Nesbit helped set it up. Weir lived in Charlottesville after his playing days working as a representative for Ballantine Beer and stayed in touch with many Cavalier football alumni. Weir not only organized it, but he played and coached the alumni from the very beginning. The program still honors Rock Weir Award winners every spring to recognize the most improved players from spring practice.

Andy Selfridge (Class of ’71), a stalwart defensive end at UVa said, “I remember the first time I met Rock. I would try to get a beer and Rock would have Ballantine beer there. Even then, my uncultured taste buds knew that this was not the premiere beer in town. And Rock’s retort was always, ‘Hey, beer is beer.'”

Selfridge continued: “I don’t think the name ‘Rock’ was applied by accident. He was a pretty tough guy. He played with Joe Palumbo, Chief Nesbitt, and Carl Smith” who were ironmen of the late 1940’s and early 50’s teams under coach Art Guepe. “I always knew he was one of the tough, old guys who had the feeling that ‘Hey punk, you have a lot to live up to.'”

|

|

UVa’s Varsity-Alumni Game in 1961. (Courtesy Virginia Athletics Media Relations) |

“And he loved the University of Virginia,” Arnette recalled. “I mean he loved it.”

“[Weir] was the leader of the alumni game, and was the coach. The offense got put together over the course of about 12 hours for the alumni,” Selfridge estimated.

“Or about 12 minutes,” Arnette deadpanned.

One of the alumni who didn’t need much in the way of game-planning was Ralph “Buddy” Shoaf (Class of ’50), who was playing for the Redskins. Shoaf was a middleweight boxer in the Marine Corps during World War II and at UVa beginning in 1946. According to Nesbit, “He was phenomenal.” Shoaf went undefeated in his first seven college fights and rose to No. 2 in the NCAA heavyweight division.

“Buddy Shoaf was the best boxer on the East Coast. Tough as nails. He was always on the kickoff team [during Varsity-Alumni Games]. He was coming down the field and just hell-bent on getting whoever got the ball,” Arnette said.

“His nickname was The Sandman,” according to Selfridge. “From his boxing days, as he would put opponents to sleep.”

Growing Popularity

After the alumni dismantled the varsity 41-0 in the first contest in 1953, the popularity of the event began to grow. It started to include more than just alumni living near Charlottesville. Charley Mott (Class of ’51), and a teammate of Nesbit and Weir, says, “Bob Weir was responsible for getting everybody together. And it brought a lot of people back.”

|

|

Bill Dudley (35) in 1941. |

After serving in the Korean War, Mott lived in Huntington, West Virginia, and traveled along with fellow alumnus Johnny Thomas back to the alumni games. In fact, alumni were returning from all parts of the country for this special new event. “With Bill Dudley, he drew the attention of everyone. He probably drew about half the crowd to see the game, just being there,” Mott said. “It was a thrill to be playing with him.”

“Bullet” Bill Dudley, the 1941 All-American and Maxwell Trophy winner, returned to play for the alumni teams until his early 50’s. At one of Arnette’s first games as an alumnus he recalls, “Bill Dudley was a kicker. And I’m used to holding the ball like this.” Arnette bends down to show how most holders prepared for the soccer-style kicks of the modern era. “I’m used to a guy going back like this and coming through and kicking it. And he’s standing right here,” Arnette describes as if Dudley is standing directly over his shoulder looking down at him. “I’m looking around and he says ‘I’m ready.’ I said ‘What?’ And he says, ‘I’m ready. Snap it.’ And he just rocked back like this and never took a step and kicked it. And guess what, he could kick it through. And I’ll never forget that.”

Oh, and the superstar who began his playing days at UVa in the 1930’s with a leather helmet? He refused, even in the 1960s, to wear a helmet with a facemask during the Varsity-Alumni games. With Shoaf and Dudley on the alumni side, toughness was never in question.

As the event grew, Ed Henry (Class of ’51) was one of the main organizers on the alumni side with Rock Weir. Henry played football for the Cavaliers in the Art Guepe era, but says of the Varsity-Alumni Games that “I had more playing time in those games than I did in the real games. Henry, who would later be an assistant on the early George Welsh teams, said that former UVa coach Ned McDonald commented to him “Why didn’t you play like that when you were [an undergraduate)?”

“Charlie Ellis played QB for the alumni side for several years,” Henry remembers. But the highlights of those earlier years were “Gene Schroeder who played safety for the Chicago Bears” and Bill Dudley. Henry was such a fan of Dudley’s as a youngster he said, “I remember keeping a picture of him over my bed when I was in high school.”

In addition to those players, more professional stars such as the Detroit Lions’ Bob Miller (UVa Class of ’52) who won NFL championships in 1952, ’53, and ’57 and Henry Jordan (UVa Class of ’57) who won the first two Super Bowls with the Green Bay Packers returned to play in the Varsity-Alumni Game in 1956 and ’57.

As the years went on, the game continued to grow in popularity. Twelve years into its history, Arnette joined the action as a member of the varsity.

|

|

Gene Arnette in 1968. |

Arnette was born and raised in Charlottesville and attended Lane High School. He never dreamed of attending UVa, as he grew up in an area with very few college graduates. But he had two high school coaches, Tommy Theodose and Joe Bingler (UVa Class of ’54) that believed in him as both an athlete and a person and encouraged him to excel in football. “We had the longest high school winning streak in America,” Arnette marvels. The football stadium at Charlottesville High School bears Theodose’s name to this day.

Greg Shelly, a roommate on a recruiting trip to Duke, became a life-long friend to Arnette and the two spoke of attending UVa together. But the biggest influence on Arnette was Dr. Frank McCue, the renowned surgeon who performed surgery on injured high school athletes across the state. McCue encouraged Arnette to stay in state, no matter where he decided to go [UVa, W&M, VPI, VMI, or Richmond]. Arnette made that decision just a few years after UVa had lost a then-NCAA-record 28 consecutive games – a decision that may have shocked a few.

“We didn’t have many scholarships,” according to Arnette. “We had 18 on offense and 18 on defense.” This was at a time where many ACC teams had almost 90 scholarship players. When visiting second-ranked Purdue in 1968, Arnette recalled thinking during warmups, “Gee, they’re not that big. And then we saw, they were just the kick returners. The next thing you know, they bring out the real team.” After that 44-6 defeat, Virginia would lose only twice more that season in route to a 7-3 record, only the program’s second-winning season in 17 years.

Arnette reveals, “We had a good bunch. Our last year we knew that we had a chance to win. And everybody was living all over campus. We had a team meeting and we told [coach George Blackburn that we wanted] to leave. We said ‘We’ve got a real chance here. Instead of running around with fraternity mates and apartment mates, we’re gonna tell the coach that we wanna go back in the dorms.’ There were only three options: live in the dorms, live on the Lawn, or get married. Can you believe the players decided to do that? It came back to pay great benefits. And the guy we loved the most was George Blackburn.”

|

|

UVa’s Varsity-Alumni Game in 1961. (Courtesy Virginia Athletics Media Relations) |

This story does not surprise Selfridge, who remains a close friend of Arnette’s. Selfridge was, according to his own accounts, “from Northwest Virginia. Also known as Cleveland, Ohio.” Former UVa assistant coach Don Lawrence, who had spent time on the staff at the University of Cincinnati, was “a Cleveland guy” and recruited several Ohio high school players to the University. Lawrence offered Selfridge a scholarship, and his options at the time both started with a “V.” According to Selfridge, “it was either Virginia or Vietnam. So I chose the former.”

As Selfridge retells the days of the Varsity-Alumni game, “Festivities usually started on Wednesdays. And the alumni didn’t know who would show up. Guys just drifted in for a faux practice. By Friday, at the practice field a car would pull in and somebody would yell ‘Alright! So-and-so is here!’ And the enthusiasm started to build,” Selfridge fondly remembered as he sat up straighter in his chair. “And some guys would just show up Saturday morning.”

A few alumni, who asked to remain anonymous, recalled that after the Friday practices the festivities would continue at Alumni Hall late into the night. Gilbert “Gilly” Sullivan, a UVa quarterback in the 1940s, and former Director of the Alumni Association, was one of the greatest supporters of the Virginia football team. He also helped develop the Virginia Student Aid Foundation, now known as the Virginia Athletics Foundation. Jane Weir, the wife of the late Mr. Weir, recalls, “They all had a good time on Friday nights and they still beat [the Varsity].”

|

|

A shot from the Alumni Game in 1961. (Courtesy Virginia Athletics Media Relations) |

“Calling Rock the coach may not have been the most correct term,” Arnette joked. “Probably the maitre’ d’,” exclaimed Selfridge capping it off with the punch line: “You had more than 100 guys show up!” So were there complaints on the alumni side about playing time? Selfridge said, “Eh, people wanted to get their licks in, but as the novelty wore off it was more of an issue of who’s still willing to go in and finish this off. But when Chuck Hammer [Class of ’69] walked onto the field, the Varsity knew someone was going to get hit hard,” Selfridge laughs.

Competition Gets Tough

In the late 1960’s, UVa started to put more and more players into the professional ranks. “People are wondering who’s gonna show up from the NFL,” said Selfridge. Several professional players did return including Jim Copeland (UVa Class of ’67 and a former Virginia Athletics Director), a lineman for the Cleveland Browns from 1967-74, Bob Kowalkowski (UVa Class of ’65), an offensive guard for the Detroit Lions and Green Bay Packers from 1966-77, and Sonny Randle (UVa Class of ’59) a wide receiver with the Cardinals, 49ers, and others from 1959-68.

One of Selfridge’s funniest stories is about the NFL-hardened Kowalkowski and his penchant for mental tactics and intimidating his opponents – even those still in the college ranks. “His favorite thing when he showed up here a day or so before the Spring Game, was that he’d go down to the equipment room [walking amongst all the varsity players]. He had a hell of a build, 250 pounds and carved out of granite. He’d go get a jock strap from Bob Goodman, the equipment manager, and he’d come strolling through the halls of University Hall with muscles rippling for everyone to see. It was quite an intimidation factor. He was like a gladiator.”

How did the alumni, on such short practice time, set up their blocking schemes? According to Selfridge, “It was cat blocking. They’d look at each other and say ‘You block this cat, and I’ll block that cat.'” Yes, the 70’s were just getting into full swing.

An Unbalanced Line

The line for the alumni in some of the 70’s consisted of Copeland, Kowalkowski, and Greg Shelly (the 1968 Jacobs Award-winner), Chuck Hammer (a 1968 All-ACC guard), Dan Ryczek (an All-ACC center and lineman for the Atlanta Falcons) Arnette at quarterback, and Jeff Anderson (Washington Redskins fullback in 1968), and Frank Quayle (Denver Broncos running back in 1968) in the backfield. Oh, and the aforementioned four-time All-Pro receiver, Randle.

“Gene always had a good game,” Selfridge recalls. “But what I remember most is that they ran an unbalanced line. Here I am, a defensive tackle, all of 208 pounds, and I’m lined up over Copeland and Kowalkowski.” Selfridge was a first-team All-ACC defensive tackle for the Hoos in 1971, and would later play for the Bills, Dolphins, and Giants for six years. So he was no slouch. “They double-teamed me and I get rolled up and I remember walking back to the defensive huddle and I was walking past the defensive backs because they rolled me 15 yards down the field,” said Selfridge while shaking his head.

“It was an All-Star game,” said Arnette. The varsity squad’s defensive line from 1969-71 was a well-coached unit and they were impressing the alumni. “The way you blitzed, you brought everybody but the waterboy,” says Arnette as he lauds the Selfridge-led defense. “We had a defense that was third in the country defensively,” Selfridge says. “Coach [Don] Lawrence [UVa’s head coach from 1971-73] was doing stuff the pros didn’t do until the mid-eighties, with nickel defenses.”

Arnette remembers from his alumni days, playing against Selfridge, “We were going down the field and we were having trouble because they were in a 4-4 or a 4-3 and one of our players said ‘Let’s go unbalanced.’ And then we put two pros and two All-ACC guys on that side of the field, with Quayle and Anderson in the backfield and [Selfridge] was on roller skates.”

“It was a good dose of humility,” Selfridge now admits.

Crowded House

Results were also showing up at the ticket booth. “We used to get five or six thousand people in the stands,” according to Selfridge. For one dollar, fans could buy a ticket the day before the game which also allowed them to bring a date. At a time when UVa had no female students, this became one of the most-anticipated social events of the year.

The stories from Selfridge and Arnette flow abundantly about the spring games in those days. Selfridge says, “Coach Ned McDonald, the defensive line coach at the time, he was the best. He sees Kowalkowski, an offensive lineman in the NFL at the time, go in to the spring game as a defensive end. Coach Mac yells to everyone on the field, ‘It looks like the Rock is out to win this one. He’s got Big Kowal out on the defensive line!’ Our best hope was Abby Sallenger, our biggest offensive lineman, who was about 6’6″ and 245 pounds probably.”

Selfridge, in his best southern accent, imitates the Texas-bred McDonald as he sees Sallenger line up against the intimidating Kowalkowski, “Come on Ay-bee, heet ’em Aybee! Come on Ay-bee!” Then Selfridge slumps in his chair, his still-accented voice now changing from enthusiasm to disappointment, “Heet ’em Ay-bee … Oooooh Ay-bee. Geet up Ay-bee. Geet up.” The varsity, according to Selfridge, knew “they had to take their medicine.”

“This went on all game long,” Arnette said. “But after the game we were all close friends and we would sit and talk [with the Varsity].”

|

|

Sonny Randle in 1959. |

Passing Attack

Adding even more flavor to the game, Arnette tells the story of Sonny Randle’s return as an alumnus. “Sonny would go in the game with his Cardinal helmet on.” In fact several of the alumni would wear their NFL helmets so that one side of the field would be peppered with Cardinals, Lions, Browns, Redskins and other helmets.”

Arnette continued: “And we’d call a play and [Randle] would say ‘No, no, here’s what we’re gonna do.’ And everybody in the huddle would look up.” In those few hours during the spring game Arnette fondly remembers, “He taught me more about receiving than anybody I’ve ever seen. Sonny said, ‘I’m gonna go down at that back that’s got me and I’m not running away from him. I’m running right at him. As soon as you see me hit him, if you see him on my inside shoulder, you throw it to my outside and make sure the ball is there.’ And guess what? It worked. Every. Single. Time. It worked.”

Alumni Games Start to Fade

Frank Quayle reminisced about those games by saying, “The highlight for me was catching up with former teammates and in particular, joining that group in the huddle to see if we still had it. Could we move the ball?”

But he also knew the game would not last for too long. “We were all a bit nervous about sustaining a meaningful injury. A little like going out to the Rockies to ski. You loved doing it but in the back of your mind you didn’t want to need crutches when you were getting back on the plane to fly home.”

The University was not the only school holding a Varsity-Alumni Game at the time. The Fighting Irish of Notre Dame began a similar contest more than 20 years before UVa. The May 15, 1967 issue of Sports Illustrated revealed, “The Oldtimers game was a brainstorm of Knute Rockne. It has been played every year but two since 1929 as a service to Notre Dame nostalgics. It does not, unfortunately, do what it was cut out to do – provide the varsity with some revealing competition at the conclusion of spring practice.”

While the Notre Dame game was broadcast nationally by ABC that year, it was the beginning of the end of a once useful, and inspiring, event.

David Sloan (Class of ’77) remembered those days fondly: “I was fortunate to get to play in one of the last Varsity-Alumni games for the legendary alumni coach Rock Weir. I can remember walking onto the field to play the game with a couple of old players who were actually smoking cigarettes and having a Bloody Mary! I also remember Rock having a team pre-game meal the night before the game … oysters and Ballantine Beer! It was fabulous.”

Unfortunately, the NFL alumni returning to the spring festivities in the late 1970’s were becoming few and far between. NFL teams frowned on their players participating in such alumni games and began to prohibit them in their player contracts.

|

|

Dick Bestwick in 1979. |

Bestwick Changes With the Times

The once-thriving competition began to take a decided turn in the varsity’s direction. Either that, or the participants did not want the crowd to go home disappointed. Former UVa Coach Dick Bestwick (1976-81) said, “I ended it. I knew it didn’t do anything to help the program. It was a farce. It was hard to play as well as you wanted to play because you wanted it to be a good game that people could enjoy. It was just a chance for some alumni to have some fun.”

While the Varsity-Alumni game was created due to a dearth of scholarship athletes, by the time Bestwick got to Virginia, the team’s scholarship numbers had grown to greater than 85. “I don’t know when it started, only when it ended,” Bestwick joked. He had redshirted the first players in UVa history. This led to older, more experienced players which even further separated the talent levels between the two squads.

Referring to the later years of the contest Nesbitt admitted: “We were lucky nobody got seriously hurt (from the alumni side). They weren’t in playing shape. And if they played two or three plays that was it. But it was fun seeing them play. You had a lot of laughs.”

But for the first few years, the game was good for the varsity players as it gave them outside competition to test their mettle against.

Still, the 1979 game would be the last. The Varsity-Alumni game lasted 27 years, “And I can tell you, that was a pretty good span,” said Selfridge. Alumni football games were coming to an end at other college campuses too, but not before one last unforgettable moment. Sloan recalls, “One of the oldest alumni players still suiting up for games was Buddy Shoaf [who was in his mid-50s]. Buddy lined up at tailback near the goal line and when they handed the ball to him, the defense just dropped to the ground and he just pranced into the end zone for a touchdown!”

|

|

UVa’s Varsity-Alumni Game in 1961. (Courtesy Virginia Athletics Media Relations) |

Arnette remembers fondly, “At the very end of one of the last games he came onto the field at the 3-yard line, because all the Alumni wanted him to score. And the entire defensive line laid down so that he could score.” Handled like true Virginia gentleman, who knew that the game was about more than just one-upping your foe.

Quayle laments, “We were all a bit disappointed when the Alumni game was done away with but I remember thinking the timing was right for me. I recognized the time had come when there was a far greater chance of my getting hurt then there was of my breaking away for a long touchdown. A lot of the former players were unhappy about it but all things considered the right decision was made.”

Sloan adds, “College football and basketball have lost their innocence, in my opinion, and it’s important to remember that it’s not just about the money.”

Imagine what would it be like today if UVa alumni such as Matt Schaub, James Farrior, Ronde Barber, Chris Long , Eugene Monroe , D’Brickashaw Ferguson, Heath Miller, Chris Canty, and Thomas Jones returned for a contest against Mike London’s varsity squad. “I think {the varsity] would like to test their value on the open market and see how they measure up,” Selfridge imagines.

Thinking back about his last varsity team and the chances he had to rekindle those memories during the Varsity-Alumni Games, Arnette passionately explains: “We were like a band of brothers. It was a close-knit group. And I’m sorry the game went away.”

About The Author: Kevin Edds is the Writer/Director of the documentary Wahoowa: The History of Virginia Cavalier Football. For more information on the film, please visit www.UVaFootballHistory.com. TheSabre.com periodically features articles on the history of UVa football where Edds, an alumnus, highlights some of the most interesting moments in the more than 120-year history of the South’s oldest football program. Email Kevin here.

Wahoowa: The History of Virginia Cavalier Football |

|

|

|