|

|

Frank Quayle’s 1968 yearbook photo. |

Frank Quayle is one of the all-time greats in Cavalier football history and one of only six Virginia players to have his number (24) retired. In just three years and 30 games, Quayle rushed for 2,695 yards and caught 83 passes for 1,145 yards. His Virginia record of 4,981 all-purpose yards still stands today.

Quayle’s mark in UVa and local history is not isolated only to his time as a player. Quayle has been a fixture in Charlottesville for decades as a realtor with Roy Wheeler in Charlottesville and as a color analyst in the broadcast booth on football Saturdays. And recently at a ceremony in Bryant Hall, the UVa Football Alumni Club named him the 2012 recipient of the Order of the Crossed Sabres Award, which recognizes service and dedication to Virginia football.

As a player, Quayle is still listed in many places throughout the UVa and ACC record books. Quayle is the ACC’s all-time leader for average yards per game for a season (186.9 ypg) and for a career (163 ypg). And, as briefly mentioned above, Quayle continues to hold the top spot for all-purpose yards in a career at UVa with 4,981 – ahead of legendary running backs Tiki Barber, Thomas Jones and John Papit. His 1,869 all-purpose yards in 1968 puts him third all-time in history, behind just Thomas Jones (2,054 in 1999) and Tiki Barber (1,906 in 1995). Quayle is also tied with Thomas Jones for second in single game rushing (221 yards in 1966), behind only John Papit’s (224 yards in 1948).

Quayle received a number of other accolades during his career too. In 1968, he was named ACC Player of the Year and ACC Athlete of the year while leading the conference with 84 points scored. In 1966 he led the nation in all purpose yards as well. Quayle achieved 10 100+ yard rushing games during his career, which spanned just 3 seasons due to freshman ineligibility rules at the time.

Quayle played briefly in the NFL and was the 113th pick overall by the Denver Broncos in 1969. Quayle played one year with the Broncos, appearing in 11 games and starting two. That year, Quayle carried the ball 57 times for 183 yards and caught 11 passes for 167 yards, including a 71-yarder, which was the longest in the NFL that season. In an earlier interview with Kevin Edds for his documentary, Wahoowa: The History of UVa Football, Quayle discussed his short professional football career:

|

|

Quayle while with the Denver Broncos in 1969. |

“I was drafted by Denver and actually got to start five games my first year but I only got on the field when Floyd Little was injured. In our second game we were playing the Jets then reigning world champs. It was on national TV (something I had very little exposure to) and Little went down early in the third quarter and on my very first run in the NFL I broke a couple of tackles, picked up a key first down and we drove to score the tying TD. We went on to upset the Jets it what probably turned out (much too my surprise and disappointment) to be my NFL highlight. Denver wasn’t very good – we finished 7-8-1 and I was frustrated recognizing Little was the guy and I would only get an opportunity as his backup.

“At the end of the season I told Coach Saban I was unhappy to just be a backup. I could tell he wasn’t happy with me not accepting the role I was supposed to play. Early the next summer I was traded to the Jets and when the regular season started I was put on their training team at $250 a week – Coach Webank was also the general manager and infamously tight – and I told him I wasn’t going to hang around for such a pittance. As you can see I was pretty full of myself at the time. I got a shot the next year with Miami and was cut the week before the regular season where they went on to go 17-0.

“Obviously not making it in the NFL hurt at the time but it enabled me to get on with my life and get a foothold in the business world that proved to pay big dividends down the road. I am a big believer that things work out for the best. Pay in the NFL was nothing like it is today. The average salary was around $18,000 per year; that is pretty hard to imagine these days when the minimum salary is around $20,000 per game.”

Originally from Garden City, New York, Quayle has been a mainstay of Charlottesville since the completion of his professional football career. After a brief one-year stint working with the UVa athletic department, Quayle began working in real estate for Roy Wheeler Company in 1973. Shortly after the passing of its founder, Roy Wheeler, Quayle purchased the company in 1976 and continues to serve as its president and Realtor for large estates and fine properties in the area.

Quayle recently completed a 29-year run as the color analyst for UVa Football and the Virginia Sports Network, working alongside play-by-play broadcasters Mac McDonald, Warren Swain and Dave Koehn. Quayle worked all but two of 348 contests over that span. During the recent Chick-fil-A Bowl in Atlanta on Dec. 31, Quayle announced it would be his final game in the broadcast booth. His knowledge and passion for the game will be missed.

More On Quayle |

|

Here are some more links featuring Frank Quayle! |

“I have had a front row seat that has enabled me to enjoy some wonderful eras of Virginia football,” Quayle told VirginiaSports.com in an earlier release. “It has been a great run for me, and I feel so fortunate to have been around this year to see the renaissance of Virginia football under Coach London. A highlight has been sharing my passion for college football, the University of Virginia, and UVa football with Virginia’s wonderful fans across the Commonwealth on Saturdays.”

Current UVa football play-by-play voice Dave Koehn quickly appreciated Quayle’s work in the booth and on the field.

“Being someone who came from out of the program and didn’t have maybe the background people who grew up around UVa had, when I got here was tasked first with trying to learn that history. That was one of the first things I tried to do when I got this job. Frank’s name continues to show up … and [he] played for the Broncos, so that gave him a little bit of street cred from my perspective. But it didn’t take long to realize what the guy meant to the program,” Koehn said. “Then you hear numbers, like the fact that he’s still the all-purpose yardage leader in the ACC, from way back then when they didn’t play as many games. You start to compile these stories and these numbers and everything from people and you realize how great he was. But even with that all said, I had a moment when I realized working with him just how amazing he was a standpoint of his playing days.

“We were sitting in Scott Stadium – I don’t remember which game it was. But suddenly some footage of him popped up on the Jumbo screen,” Koehn continued. “A lot of the time when I’m immersed in the game I’m not paying attention to what’s going on outside of looking at statistics or something for my next segment. But it’s an ad break and I hear everybody cheering in the stadium, and they start looking back at us. I kind of look up at the screen and I see footage of Frank in the 1960’s – this young guy just slashing by guys. And I don’t think it really set in until that moment just how prolific he was. I knew Frank as the broadcaster. You kind of had to sit back and appreciate and enjoy that moment. It was pretty neat to be standing next to him, and having worked with this guy, and you see him in a different vein. I think that was the moment I had a revelation of sorts to how amazing he was as a player. It’s hard to grasp that sometimes, having not seen it in person or grown up around the program hearing the stories. But it doesn’t take long to realize it.”

|

|

UVa radio crew: Chris Slade, Dave Koehn and Frank Quayle. |

Koehn also quickly picked up on Quayle’s passion for Virginia football. I asked Koehn about Quayle’s animated excitement in the booth – I heard stories in the old days about when they’d actually turn off his microphone – as a broadcaster.

“It’s funny that you say that. One of the things I think ingratiated him with fans was the fact that would wear his passion on his sleeve, and he cared so much about that program. I think his passion for UVa is so readily evident, and I think that does manifest itself through the broadcast sometimes. I think the first couple of years I was in the booth we didn’t have a whole lot of great moments, unfortunately. So I didn’t see that as much from Frank. But this last year we got to see it a little bit more. [Laughing] Yes, he’s definitely very passionate and sometimes very vocal about it in the broadcast booth,” Koehn said. “On that line of thought, one thing that was also kind of neat from working with Frank this year was when we beat Florida State. Seeing the impact and effect that had on him was pretty neat. He’ll probably kill me for saying this, but I saw a tear in his eye. It was amazing. He really lives and breathes the program. Yeah, he was pretty animated in the broadcast booth, particularly when things were going well and there was excitement on the field.”

Quayle, a strong family man, has been married for 41 years to his wife Peggy. They have three children; Jay (39, Princeton and Duke), Willie (33, Virginia) and Kelly (29, Princeton and Stanford). They have five grandchildren with a sixth on the way in a couple of weeks. Jay, Willie and Kelly all played collegiate lacrosse, and most interestingly they all played in national title games. Willie was on the 1999 National Champion team while at Virginia, while Jay and Kelly both played for the national title with Princeton.

With all of that in mind, it’s time for the interview. Enjoy.

The Sabre Interview

Mike: You played before freshmen were eligible to play. You’re still UVa football’s career all-purpose yards leader, over some great modern day backs like Terry Kirby, Barry Word, Tiki Barber, and Thomas Jones. And you did it playing only 10 games per, in just three seasons, and with no bowl appearances. It appears remarkable that the record still stands considering all of the great backs who have played over the last couple of decades.

Mike: You played before freshmen were eligible to play. You’re still UVa football’s career all-purpose yards leader, over some great modern day backs like Terry Kirby, Barry Word, Tiki Barber, and Thomas Jones. And you did it playing only 10 games per, in just three seasons, and with no bowl appearances. It appears remarkable that the record still stands considering all of the great backs who have played over the last couple of decades.

|

|

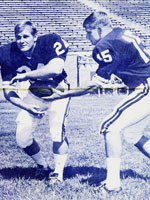

Virginia coach George Blackburn with Wahoo standout Frank Quayle. |

QUAYLE: Nelson Yarbrough heads up the UVa Alumni Football Club and was the quarterback at UVa in the mid-50’s. I came across something that mentioned he was number one in the conference in passing. It was about the seventh game of the year and he had 580 yards passing. The game has obviously changed dramatically. But I had a coach, George Blackburn, who was so far ahead of what was going on at the time. We had as close to a spread offense as you could have back in the 60’s, so I benefitted from that greatly. He designed plays where three to seven times a game I’d get the ball and there wouldn’t be a defender within three or four yards of me.

Mike: Have you ever wondered what would your career numbers have looked like had you played all four years?

Mike: Have you ever wondered what would your career numbers have looked like had you played all four years?

QUAYLE: [Laughs] You can’t play that game. I could have gotten hurt playing as a freshman and never stepped back onto the field. I don’t spend a whole lot of time on things that could’ve, would’ve.

Mike: Is freshmen eligibility a good thing, or has it hurt the athletes’ ability to adjust to college life and academic regimen?

Mike: Is freshmen eligibility a good thing, or has it hurt the athletes’ ability to adjust to college life and academic regimen?

QUAYLE: I think that’s a good point. It was the early 70’s where they implemented that freshmen could play. The big positive I saw [without freshmen eligibility] was that when you come in with your class of recruits, you are an entity – you’re not mixed with the other 70 or 80 players. We had this bond for the four years we were there, and for the alumni games. We would all go out on the field as a unit. I thought there were wonderful benefits to me for that. The adjustment … I’m going to guess they do a better job [today] of introducing kids to the importance of studying and discipline to handle all of the things you have on your plate. I can’t imagine – I struggled as a first year with my grades and so many different issues. If I had been flying to games and participating in that, it could have pushed me over the edge and I’d fallen off the cliff.

Mike: How would players of your era stack up to players of today, particularly the prime players like yourself, Bob Davis, Don Parker, etc. who could play anywhere at any time?

Mike: How would players of your era stack up to players of today, particularly the prime players like yourself, Bob Davis, Don Parker, etc. who could play anywhere at any time?

QUAYLE: I’ve always thought there’s no way to properly compare eras. Bill Dudley would have been an extraordinary football player in any era. These guys, they’re so much more than size, speed, and strength – there’s the drive, the want to, the passion for the game. Those guys had it, and they would have done what they needed to do to find a spot. One interesting position, running back – there’s no difference today in the size of running backs. With some exceptions, almost all of the great running backs are within 5’9″ and 5’11”. I always laugh when I hear Kevin Parks get criticism with words like diminutive or tiny. As low to the ground he is, and as powerful as he is – 190 pounds and you’re 5’7″ – that lines up very well with somebody who is 6’2″ and 240. To me, the great running backs are low to the ground, bow-legged, and they’ve got extraordinary balance. And they are as powerful at those sizes because of being lower to the ground than those who are 6’2″ to 6’4″.

Mike: Did you have a favorite college growing up, or was it primarily just professional football coverage on television and not much exposure to college football?

Mike: Did you have a favorite college growing up, or was it primarily just professional football coverage on television and not much exposure to college football?

QUAYLE: I grew up in Garden City, New York, about 20 miles from Manhattan. There clearly was no team [in our area] like UVa for Charlottesville or Penn State for the State College kids. You were a Giants fan in the late 60’s growing up – the Cleveland Browns I remember because of Jimmy Brown. You’d hear of college kids, but Long Island is unique in how pro sport-focused it is.

Mike: So not much knowledge of Virginia growing up?

Mike: So not much knowledge of Virginia growing up?

QUAYLE: I grew up in a town where a lot of kids went off to Ivy League schools. I spent a year in prep school, which I needed to do after my four years of high school. It was a Dartmouth Alumnus who set me up, so that’s where I thought I would be going. I would watch teams like Notre Dame that would be on television. Oklahoma had an extraordinary program. But you just thought those were things – it was hard to imagine [going there]. Long Island is 120 miles long and back then had 125 public high schools.

|

|

Frank Quayle against Maryland in 1967. |

I remember doing a report one time for a class on where those kids go to school. If you took the military academies out of the mix, there were only three kids from those 125 high schools playing major college football back then. It’s just extraordinary. I attributed it to the [high school] coaches. Back then, those guys got paid very well for teaching and had a wonderful retirement program. They weren’t hungry to become a college coach. They liked what they did. They didn’t put any time into it once practice was over. But when I came down here I saw all of the high school coaches that would go to seminars and do things during the summer. They’d start practice Aug. 1. We didn’t start practice until after Labor Day. We could only have eight games and there was no playoff. So, it was sheltered football.

Mike: Exceptional high school football players today have very little privacy and are contacted by a number of people to include recruiting services, the media, friends, and college coaching staffs. What was recruiting like during your high school years? Was it ever this intense?

Mike: Exceptional high school football players today have very little privacy and are contacted by a number of people to include recruiting services, the media, friends, and college coaching staffs. What was recruiting like during your high school years? Was it ever this intense?

QUAYLE: Coming out of high school, I maybe could have gone to a handful of schools. I had an opportunity to get a scholarship to William & Mary, but not a whole lot of programs. The finest football team I ever played for was that prep school. They brought in over 40 kids. I remember one of the first days I was there. They went around the room and you got to introduce yourself and talk about your accolades. It seemed to me that half the kids were All-State, Big 33 – extraordinary things. Now I had made the All-League Team, and there were probably 16 conferences on Long Island, so my achievements were diminished dramatically in the face of those guys. I did well in that setting, and I got on the radar of a lot of schools. All of the sudden Notre Dame was coming. I flew out to Arizona. Duke was a school I paid a lot of attention to.

Mike: How did UVa get on your radar?

Mike: How did UVa get on your radar?

QUAYLE: My little league coach, Armand Prusmack, had been a professor at NYU and was a wonderful guy. He had two sons, Jon Prusmack and Bobby Prusmack. Jon went to Notre Dame and started at fullback, and Bobby came to UVa. Bobby was a lacrosse player as well. He played a major role [in my coming to UVa]. I looked up to him. We called him ‘The Neck’. He had a 21-inch neck and everybody couldn’t believe this kid. Sports Illustrated wrote an article on him and a guy named Bob Dunphey. They were both in the same fraternity house and they would have this competition – would Dunphey’s biceps be bigger than Bobby’s neck. One was a 21 and the other 20.5. It was extraordinary how developed they were. They talked to the coaches about me and got me on the radar. When I first started talking to the football department, Bill Elias was the head coach. But it was Gene Corrigan who probably played a bigger role in my saying UVa is where I want to come to. Corrigan was the lacrosse coach here and one of them most personable people you would ever meet.

|

|

Frank Quayle is one of just six UVa players to have his number (24) retired. |

Mike: Did Coach Blackburn or Bob Davis have any bearing on your interest in UVa?

Mike: Did Coach Blackburn or Bob Davis have any bearing on your interest in UVa?

QUAYLE: Bill Elias was the coach who initially started the process. I cannot even think of the gentleman who was the recruiter for the Long Island area, but that’s who came up to visit. Within about three weeks of when I had a trip planned there, I got a letter saying that Coach Elias had taken the position at the Naval Academy. But by that time, Coach Corrigan and I had talked and I was enamored with him. So then I made the trip and that’s when I met Coach Blackburn, who had just been named the coach.

Mike: Did you know who Bob Davis was at the time?

Mike: Did you know who Bob Davis was at the time?

QUAYLE: It’s interesting, and a lot has been made of how ignorant I was about the UVa program. And I was. There was a lot of talk the year before about the success they had, and the offense they had. They beat Army when Army was a very good football team. That summer I remember Sports Illustrated picked Virginia to be 20th in the country and Bob Davis was on a lot of teams’ picks to be the All-American quarterback. So all I had on my mind is that I was going to a program that was on the move.

Mike: How many schools did you visit and what schools had interest and vice-versa?

Mike: How many schools did you visit and what schools had interest and vice-versa?

QUAYLE: My senior year in high school, William & Mary was the only school I visited. My parents wanted me to go to a Catholic school, so Boston College was on the radar. But as a senior in high school I didn’t get invited to go there. Dayton, I could have gone out to. Notre Dame didn’t pay any attention to me.

So, the next year during the football season, I didn’t hear from anybody. It wasn’t until January or February until schools would talk to me. The Prep School I went to would only give me two weekends off, so I went to UVa and then out to Arizona – not thinking I was going to go to Arizona, but it was a fun trip. I spent a lot of time meeting with the Duke coaches. They came up a couple of times. I think I could have gone on trips to those schools if they were on my radar. I could have taken a trip to Syracuse, but had no interest in that. I finally got on Boston College’s radar and could have gone there.

Mike: In today’s environment, committed recruits often assist in recruiting other players to their school of choice. How much of that happened during your time?

Mike: In today’s environment, committed recruits often assist in recruiting other players to their school of choice. How much of that happened during your time?

QUAYLE: Absolutely zero.

Mike: What about when you were a player? Did you escort recruits or have any bearing on recruits having interest in UVa?

Mike: What about when you were a player? Did you escort recruits or have any bearing on recruits having interest in UVa?

QUAYLE: I’d tell [the coaches] about some high school kids back at Garden City. [For instance], there were two kids, Ricky Frisbee and Donnie McCauley. And so they would come for a visit, and naturally I’m put in charge of their weekend. Donnie would have loved to have come here, but he didn’t have 1,000 on his college boards – he had like 980. The coaches wanted Ricky Frisbee more. Ricky Frisbee goes to Harvard and Donnie’s bitterly disappointed he can’t come to UVa and he goes to Carolina. His dad sent film to the Carolina coaches to get them to look at him. Donnie MacAulay went on to have an extraordinary career with Carolina. It is so extraordinarily different today than it was back then.

Mike: How much of a toll on your body did it take to play 100% of the plays, return kickoffs and generally be the target of opposing defenses?

Mike: How much of a toll on your body did it take to play 100% of the plays, return kickoffs and generally be the target of opposing defenses?

QUAYLE: I certainly never would have given any thought to those factors. I can remember I had a signal with the backup running backs. Early on it was Donnie Seemuller and Bobby Serino, and my junior and senior year it was Dave Wyncoup. If I touched my helmet, I was gassed and wanted to come out of the game.

Mike: How many players were on a team when you played and did players need to play both ways?

Mike: How many players were on a team when you played and did players need to play both ways?

|

|

Frank Quayle was named the 1968 ACC Player of the Year. |

QUAYLE: Nobody played both ways. A couple of years before, they had those rules where you had to play both ways. Most classes had about 18 recruits, so that would give you 54 over the three years. I’d say we had about 60 on the sidelines.

Mike: How much lacrosse did you play at UVa?

Mike: How much lacrosse did you play at UVa?

QUAYLE: We had a freshman team, so I played my freshman year. My sophomore year was probably the year I played the most. As a junior, I got mono early on and in the spring played the first two games and missed maybe five games. I came on at the end for a couple. My senior year – and I feel a little bad about this – played maybe two games and then signed a contract [with the NFL]. Back then if you signed anything that had to do with a professional sport, you were done with your college career.

Mike: How much did playing lacrosse help your development as a football player?

Mike: How much did playing lacrosse help your development as a football player?

QUAYLE: I saw something recently that said Frank benefitted greatly from lacrosse, and they were referring to your ability and first step and quick acceleration. But I don’t ever remember that. In high school it was a very important sport. Back then, 50 percent of your team was made up of kids who had never seen a lacrosse stick before they arrived in college. And the other 50 percent would be Long Island or Baltimore guys who benefitted greatly from schools with wonderful lacrosse tradition.

It kept you in good shape. To me it was sort of an outlet. I was far more passionate about football than I was lacrosse, but lacrosse was like playing rugby. It was a great social thing. It was fun. Football was very unique in that practice is not fun. But the games are unlike anything else you’ve ever experienced. Lacrosse, every practice was fun because you’d be out there scrimmaging and doing the activities.

Mike: You had an asthma problem while playing at UVa. How did you counter this? What did the training staff do to help you stay on the field?

Mike: You had an asthma problem while playing at UVa. How did you counter this? What did the training staff do to help you stay on the field?

QUAYLE: I did have asthma. I felt it was blown up a little [by the media]. It became an interesting story for a reporter to talk about, so there were a lot of stories about it. I did have asthma, and I controlled it with inhalers. I talked about touching my helmet when I was gassed. I probably did that more than other people, but I’m not sure if it was about asthma or that I was just gassed.

The staff at the time would send me over to the University Hospital and do all of these allergy tests. I would have some sort of cough medicine and inhalers on the sidelines. And there were uppers in those things, so you’d get a boost from taking it and it would clear your throat.

Mike: What’s your fondest memory as a football player while at UVa?

Mike: What’s your fondest memory as a football player while at UVa?

|

|

Frank Quayle on the sidelines in 1968 |

QUAYLE: I always thought of this as a little bit embarrassing in that it was a loss, but the most memorable game in my career would have been during my sophomore year. We went down and played Georgia Tech. They were big time football at the time. They were number five in the country and were 8-0. I remember the headline of the Atlanta Constitution saying the number five team in Virginia came and played the number five team in the nation and you couldn’t tell the difference without the jerseys.

The year before I listened to [that game] on the radio, and Bobby Davis had a remarkable game down there but I think we got beat like 41-17 [42-19 was the final].

A couple of things happened in this game [the next year]. It was zero to zero at halftime. We scored a touchdown to make it 7-0 in the third quarter. As soon as they got the ball back they went roaring down the field and scored. We get the ball another time and we’re at the 3-yard line and we fumble the ball going into the end zone and they recover. But then we get the ball again and go down and we score. So, we’re ahead 13-7 and we kicked the extra point and they jump off sides. [Laughing] So, we begged Coach Blackburn to let us go for two from the one and a half yard line. They called my number. It was going to be an off-tackle play. It was clogged up there so I tried to go over the top and could tell I was going to get stopped. I turned my back to the players and threw the ball back to Bobby Davis. We had a guy wide open in the corner of the end zone and he throws it to him and he catches the ball. But, the officials said that the whistle had blown before I got the ball out of my hands.

They’re probably right. I remember seeing pictures of it after that. So now it’s 13-7, our favor. They go down the field and score and kick the extra point. It’s 14-13 [Georgia Tech]. There’s about a minute and forty seconds left in the game. Every practice at UVa, the three years I played on the varsity, we would finish up with a drill. We’d run four plays – it’s when you can’t huddle and you’re running out of time, so you run these four plays. It was different than the two minute drill in that it was these four [specific] plays you were going to run. We practiced it every practice, but this was the only time in 30 games we ever used it, and it worked. We receive the kick off and we drive down the field and get down to about the 12-yard line – with four seconds left in the game. And we’re kicking the field goal.

There’s a picture that I think is just wonderful. … First of all, it was Grant Field against the number five team and as packed as can be – which meant about 50,000 people. That was a lot of people for us to play in front of. The picture has the scoreboard, 14-13. It has 4 seconds left on it. You see our kicker line up to kick the ball from the 18-yard line. And you see the Virginia bench and they’re all holding hands. We missed the field goal and lost, but that was by far my most memorable game.

Mike: What was it like running the center/middle screen with Bob Davis at QB?

Mike: What was it like running the center/middle screen with Bob Davis at QB?

|

|

Frank Quayle with Gene Arnette in 1967. |

QUAYLE: Gene Arnette ran it too. It was an extraordinary play. I’m a little surprised you don’t see more people do it. You’d have twin backs in the backfield. The ball is snapped, and it would look just like a drop back – 8 yards. I’d run off to the corner, a little bit outside where the tight end had been, and then I’d curl back and have blockers in front of me. We must have run that play certainly 20 times in my career, maybe more. So people knew we were going to run it. But, it rarely would get stopped and would create so many opportunities. It was a brilliant play. The guy deserving the credit is Coach Blackburn and Ben Wilson, our offensive coordinator. It wasn’t too challenging a play for the quarterback, other than he wanted to make it look like it was going to be a deep pass.

Mike: You had an opportunity in your last game to break the single-season rushing record set by John Papit. Some reports state that you chose not to break the record. Most backs would take the opportunity. Why didn’t you?

Mike: You had an opportunity in your last game to break the single-season rushing record set by John Papit. Some reports state that you chose not to break the record. Most backs would take the opportunity. Why didn’t you?

QUAYLE: The last couple of days there have been some comments about that [in the media]. They really have missed what was going through my head.

Clemson was playing South Carolina and we were playing Maryland. A lot of people were following it – it was a big story. Buddy Gore [of Clemson] and I both started our sophomore year together and we played 30 games. Before the game we both had the exact number of yards. At that time we were tied for the ACC record for most yards ever. So whoever had the most yards [at the end of the game] would hold the record. Both games were going on at the same time, so people would come along the sideline and say ‘Gore has such and such.’ So now it’s the fourth quarter and their game is either over or something, and I had over 200 yards, which had only happened in the ACC two or three times. So, that accomplishment [of holding the ACC career rushing record] was mine and that meant so much more [than the UVa single season rushing record].

But, we’re trying to run out the clock and the game is still up in the air – it’s 28-23. If we get stopped and Maryland scores, we lose the game. We probably had the ball down about the 30-yard line. Back then Gene Arnette would call the plays. Coach Blackburn might give him one or two things, but Gene was a brilliant play caller. He called the play that was going to be a counter play. They were so hungry to try and get to the play that – take a step one way, come back with a trap block the other – it had a good chance of working.

Now, I’ll go back to my sophomore year. It’s the last game and we’re playing North Carolina. We won the game. There’s about 40 seconds left in the game and we’ve got the ball. [Thinking back further], Bobby Davis as a sophomore had run out the clock just by dropping back and scrambling all over the field – they couldn’t get to him. He got a lot of notoriety for it. So now [Bobby] has a similar opportunity to do that. He says, ‘I’ll take the ball here.’ He scrambles and the closing seconds of the game he gets tackled and tears up his knee. He gets operated on shortly thereafter.

|

|

Frank Quayle in 1967. |

So, I’m in the huddle, there’s 40 seconds left in the game, I’m satiated from the [ACC] accomplishment and of having a win – and Gene calls that play. I said, ‘I don’t need to carry the ball now.’ I was thinking of Bobby Davis and getting hurt on the last play of the game. So, that was more a factor than what has been said.

Mike: Do you feel the academic burden is heavier, lighter or about the same versus the late 60’s and early 70’s?

Mike: Do you feel the academic burden is heavier, lighter or about the same versus the late 60’s and early 70’s?

QUAYLE: You’ll be surprised, but my interaction with the players [while in radio] was almost nil. I’ve heard they do a good job of showing the kids what they need to do, the importance of being in class, working with tutors and all. We had tutors available, I guess. But I don’t remember using them very much. Getting an education is what you’re here for. At the time, sports to me was more important than education, but I recognized that after two to ten years, which is the most anybody’s pro career is going to be, that education is what you fall back on.

Mike: What about available majors? UVa has very few what are considered ‘jock majors,’ while other competing schools have a great number of these. Should UVa introduce easier majors for athletes?

Mike: What about available majors? UVa has very few what are considered ‘jock majors,’ while other competing schools have a great number of these. Should UVa introduce easier majors for athletes?

QUAYLE: When Coach Groh’s tenure here blew up, I had in my mind that there were some institutional issues that made it challenging. He did some wonderful things the first three or four years. In the forty or fifty years I’ve followed UVa football, his 2004 football team was the most dominant ACC school over other pre-Florida State schools. So if you just look at that pool, and if we had had [Matt] Schaub, that line and running game, and that defense, I think we would have been one of the great teams – we got to No. 6 that year.

So, where did things go wrong? And they certainly did. To me, ‘easier’ isn’t the proper term … but things that the kids can get enthused about. Anthropology is a curriculum that a high percentage of those kids are in. Somehow I don’t see them getting real excited about studying Anthropology. Where if you had some communication courses, some marketing courses – some things that they could get their arms around and be excited about and enthusiastic about, I think it would make everything so much better. And it’s silly that we don’t have some programs that are going to benefit kids going forward in their careers. I would look at why there are a high percentage of kids in Anthropology – there’s something wrong here.

Mike: Do you think Virginia should go the route of true jock majors like Physical Education and Apparel Management as is the case with other competing schools?

Mike: Do you think Virginia should go the route of true jock majors like Physical Education and Apparel Management as is the case with other competing schools?

|

|

Frank Quayle still holds UVa’s all-time record for all-purpose yards. |

QUAYLE: When you say Physical Education that makes it an easy conversation. Do we want that? It’s a scapegoat, and the senior faculty would be against that. I don’t think we have to go there. But you can come up with some programs that would be very interesting and beneficial that other schools offer and UVa fails to offer – and they’d be excited about going into the classroom.

Mike: I expect the commitment level to practice, film study, weight lifting, etc. has increased over the last several decades. Talk about the pressure now to perform in big time athletics compared to when you played. Do you think it’s more difficult now?

Mike: I expect the commitment level to practice, film study, weight lifting, etc. has increased over the last several decades. Talk about the pressure now to perform in big time athletics compared to when you played. Do you think it’s more difficult now?

QUAYLE: Well, sadly with all sports, it used to be that you played three sports in high school – you’d hang up your helmet and go to wrestling or something during the winter. And then you’d play baseball or lacrosse during the spring. Now it’s gotten to when kids are 8, 9 or 10 years old parents are so focused on their kids being able to use this as a way to get into college – the need to specialize in a sport. I think that’s a shame. Clearly [college athletes] spend a great deal more time [than in the past].

My three children all played college lacrosse – Willie played here [at UVa]. They call them minor sports, but the commitment those kids make is ten months a year. And they’re going hard 20-30 hours a week becoming the best lacrosse player – or whatever their sport is. In football we didn’t have much weight lifting, but I was a fanatic in that area. I had an advantage because I was doing it and most kids weren’t. Studying film? We would spend two to four hours a week doing that. I do understand that it’s big time athletics. I’m not sure how much pressure – the kids that are going to be successful, they are driven and they want to do everything they can to become bigger, stronger, faster, smarter football players.

Mike: Talk about your first opportunity in broadcasting and how it relates to Chris Cramer.

Mike: Talk about your first opportunity in broadcasting and how it relates to Chris Cramer.

QUAYLE: I knew Chris and he invited me to do the national lacrosse championship game when Virginia played Hopkins in 1972, so I worked with him in the booth. At one time he asked if I wanted to interview to do the play-by-play. I interviewed and must have done very poorly because I didn’t get the job. I liked Chris very much. He was a play-by-play guy. Their job is so totally different from commentary. They’re professionals. I do what guys do when you go to a game, and you see a play, and you’ve got a buddy next to you – and you make a comment about it. That doesn’t take a whole lot of technique.

Mike: Which game was the most exciting for you to call?

Mike: Which game was the most exciting for you to call?

QUAYLE: Well, clearly the Florida State game. There were so many different reasons for why that game was such a big deal. No ACC school had ever beaten Florida State. That was a huge embarrassment. It was like 28-0 or 29-0. Virginia had never beaten a No. 1 team. Interestingly, they were No. 2 that week, but they had been No. 1 from the preseason until the week before. They had the week off and somehow Nebraska jumped ahead of them. The other thing I think was remarkable about that game … first game of the year Virginia loses to Michigan on the last play of the game as the clock expires. A few weeks later, they’re playing Texas and they lose on the last play. They are one of only two or three teams in the country ever to have lost two games in a season as the time expired. No team had ever lost three games as time expired. And now [FSU] is lined up on the two or three yard line with five seconds left in the game and the clock is going to expire. They’re either going to set a record that goes down in infamy, or they’re going to be the first team in the ACC ever to beat Florida State.

It was nationally televised. I couldn’t imagine anybody who is an ACC fan, at any of the other schools except for Florida State, standing up and screaming that this is such a big, big play coming up. The culmination of excitement and meaningful things dwarfs any other game I ever did.

Another thing I find fascinating. About three or four weeks later, could have been bowl season, Warrick Dunn and two of the other Florida State guys chime in that the greatest football atmosphere they ever played in was Scott Stadium that night. Now here are guys who have played for the National Championship, they’ve played in the Sugar Bowl before 90-something-thousand fans, and the greatest atmosphere [was at Scott Stadium]. And [as a player] you don’t want to talk about a game where you got beat. For them to make that comment was extraordinary.

Mike: Which season was the most exciting for you to watch as football alum?

Mike: Which season was the most exciting for you to watch as football alum?

|

|

Check out this piece on Frank Quayle that Kevin Edds, creator of the above Wahoowa film, produced. It highlights Quayle’s magnificent accomplishments while becoming the 1968 ACC Player of the Year! |

QUAYLE: [1995] Because of that [FSU] game being so big … playing out at Michigan was extraordinary … playing down in Austin, Texas was extraordinary. And then they had a Peach Bowl against Georgia that was absolutely wonderful. We came in there as underdogs. We looked like we had won the game. Then Georgia scores [to tie]. And Demetrius Allen returns that [kick return].

You put in 29 seasons and it’s hard to be analytical. This last season certainly is in my top five seasons, and maybe my top three. It was unexpected winning at Miami, and Florida State for the first time ever. I didn’t think they were going to be a great team. Would they have a winning season? I wasn’t sure. Quarterback plays such a big role. Do we have a quarterback going into the season? You look at that season and it was as enjoyable to follow as any I can remember.

Mike: Coach Mike London seems to have a knack for motivating players to achieve more than expected.

Mike: Coach Mike London seems to have a knack for motivating players to achieve more than expected.

QUAYLE: I was a modest skeptic at first. I think he’s extraordinarily good at what he does. The kids have bought in. I love the guy and he’s just done a super job.

Mike: Which UVa football team do you believe was the best of the modern era? Some suggest 1990, a team that rose to No. 1 and played toe to toe with eventual National Champion Georgia Tech. Some might suggest 1995 with so many future professional players and last second losses as Michigan and Texas. What’s your take?

Mike: Which UVa football team do you believe was the best of the modern era? Some suggest 1990, a team that rose to No. 1 and played toe to toe with eventual National Champion Georgia Tech. Some might suggest 1995 with so many future professional players and last second losses as Michigan and Texas. What’s your take?

QUAYLE: It’s so difficult to do. I would think that most people who watched the 1990 Virginia-Georgia Tech game would think Virginia was the better team. They were ahead by two touchdowns most of the game. They did have a lot of things go against them in the second half. But, I’m skeptical that Georgia Tech was the best team in the country that year. It’s difficult to play the game on who was the best. The [1990 team] has a very good case to make. I always thought I was so fortunate [to call games during that time]. If Chris Cramer had given me the job early on, I would not have lasted 10 years, 5 years – the patience. [UVa] played ugly, terrible football during the 70’s.

I was so fortunate to come in at the time I did. Coach Welsh – I think his accomplishments were extraordinary and he doesn’t get nearly the recognition [he deserves]. I can remember his last three to five years the fans were upset with him, and how we can’t get the job done in November. I’d look and I’d say, well in November we would play three teams that were in the top 20. We were probably between the 20th and 35th best team in the country – you’re going to lose to those guys most times.

Mike: Perhaps having some distance from Welsh, and a few losing seasons rather than ‘7 or more per year,’ will give fans some perspective, an appreciation for what success is and how hard it is to come by, and allow Coach London some latitude to possibly get UVa back to that kind of success.

Mike: Perhaps having some distance from Welsh, and a few losing seasons rather than ‘7 or more per year,’ will give fans some perspective, an appreciation for what success is and how hard it is to come by, and allow Coach London some latitude to possibly get UVa back to that kind of success.

QUAYLE: I do think it’s the nature [of fans]. And I would love to think [London] gets us there. But if 12 years from now he has seven years of eight-win seasons, you’ll hear people bitching about not getting over the ‘8-win’ [barrier].

Mike: You were honored recently with the Order of the Crossed Sabres. Talk about what this means to you.

Mike: You were honored recently with the Order of the Crossed Sabres. Talk about what this means to you.

QUAYLE: I certainly was honored. What comes across to me the most is the quality of the previous recipients. From football players Joe Palumbo and Bill Dudley – Hall of Fame guys. Coach Welsh, a Hall of Fame coach and player. Philanthropist Carl Smith and his wife Hunter. The Bryant family and Bobby Butcher. Virginia has facilities that I think can compete with anybody in the country, and those who are the people you get to thank. The impact of Frank McCue and Joe Gieck – they are so revered by so many players. Those people had such a big impact on the program.

To me, it’s pretty flattering stuff to be put in that group of people. And that by far is what means the most to me.

Mike Ingalls founded TheSabre.com as a hobby in 1996 under the name VirginiaFootball.com. The site changed its name, became a business, and earned fully credentialed media status in 1998. “The Sabre Interview” appears periodically on the TheSabre.com as Mike sits down for in-depth interviews with your favorite Hoos.