About The Author: Kevin Edds is the Writer/Director of the documentary Wahoowa: The History of Virginia Cavalier Football. You can purchase the DVD from our sponsor UVA Bookstores (click here). For more information on his new film Hoos Coming to Dinner: The Virginia Cavaliers Unbelievable Rise to #1, please visit www.UVaFootballHistory.com. To Email Kevin, click here.

This is Part 2 of a three-part article series on the evolution of the ACC.

While the larger schools in the Southern Conference like UNC, Duke, Clemson, and Maryland were making regular appearances in the Orange, Sugar, and Gator Bowls, the smaller schools in the SoCon were not. They were still stuck in the world of small time football. Relations between the haves and have-nots in the SoCon began to change in 1951. Maryland was riding high at 7-0, along with Duke at 6-0, and Cotton Bowl representatives were planning a visit to College Park.

In previous seasons, permission was granted for numerous Southern Conference schools to accept bowl bids through a poll of the conference’s presidents. But in the summer of 1951, at an informal conference gathering in Chapel Hill, two-thirds of the 17 programs recommended outlawing bowl games and called for an end to spring practice in an effort to de-emphasize football.

Maryland Athletics Director and football coach Jim Tatum told a pool of reporters, “These matters will be brought up at the conference’s December meeting. Until then, our old rules are still in effect. That is, a team can go to a bowl with approval from a majority of members. Permission always has been granted in the past.”

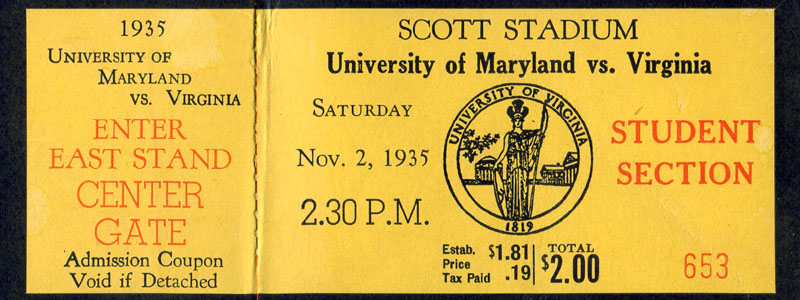

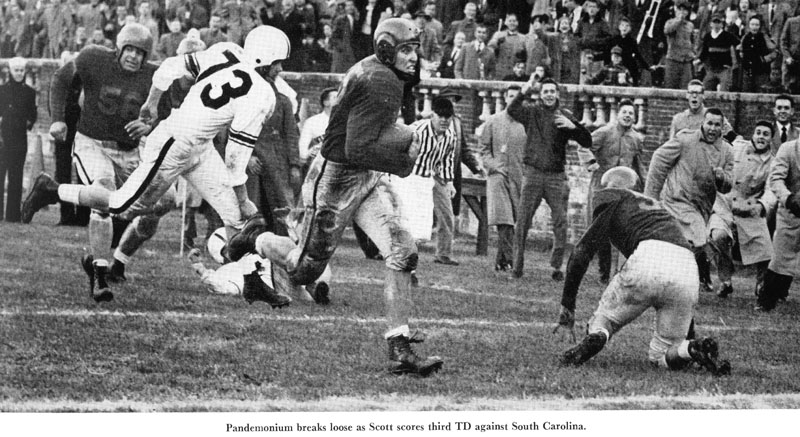

Asked about the potential of Maryland withdrawing from the Southern Conference if a bowl bid was prohibited by the presidents Tatum said: “Virginia withdrew years ago. I wonder if it has hurt them much?” Fans today who are familiar with Virginia’s struggles before coach George Welsh’s arrival would expect that the answer was “yes,” but in 1951 UVa was in the midst of arguably the best era in its history. The Cavaliers went 23-5 over the previous three seasons and received a bid to the Orange Bowl, one that it would decline to the dismay of Virginia players and supporters. Tatum’s throw-away one-liner was ominous. After the following season, UVa had but two winning campaigns over the next 30 years.

Maryland finished the 1951 regular season 9-0 and accepted a bid against 10-0 Tennessee in the Sugar Bowl. Clemson said yes to an offer to play in the Gator Bowl. Both schools did this before the Southern Conference’s annual December meeting. “Never before has a Southern Conference team failed to receive the league’s blessings to play in a bowl game,” Tatum stated. “I think the individual school should make its own decision on such matters as a bowl game.” “No matter what the final vote” Maryland President H.C. “Curly” Byrd said, the school planned to play in the Sugar Bowl anyway and accepted the bid. Clemson did the same.

On December 15th, 1951 the Southern Conference leaders gathered in Richmond. Maryland’s Byrd presented his case to the attendees in a 26-minute plea to allow his undefeated football team to play in the Sugar Bowl and continue its quest for a National Championship.

Interestingly, schools against bowl games included the “Carolina Four,” future ACC partners Duke, NC State, UNC, and Wake Forest, while South Carolina was in agreement with Maryland and Clemson. UNC President Gordon Gray chastised Clemson for asking for permission to play and then accepting the Gator Bowl bid anyway when approval was denied.

Arguing against the bowl restrictions, Clemson coach Frank Howard said, “I don’t think it’s right.” Since 1945, Southern Conference schools had participated in 14 bowl games. In 11 of those instances, the schools had accepted the bid before asking permission from the other members at their annual December meeting. Now it seemed to Maryland and Clemson that the rules were being rewritten on the fly.

After calling the issue to a vote, school presidents put their previous recommendation on banning bowl games into conference law by a 14-3 count. And in reaction to Maryland and Clemson accepting bids, the conference heads voted 12-5 to put both teams on probation for one year prohibiting them from playing programs within the conference the following season.

Another bylaw that did not receive much media attention was also passed. Presidents voted to allow an unlimited number of members in the conference, when previously it had been a maximum of eighteen.

Nation’s Best Suspended

After third-ranked 10-0 Maryland defeated No. 1 Tennessee in the Sugar Bowl, most felt the Terrapins were college football’s true champs, despite pollsters having awarded the National Championship to the Volunteers before the bowl game. Now being shut out from scheduling fellow SoCons teams the next year, Maryland’s 1952 makeshift schedule was reduced to nine games, instead of eleven as they originally intended. That included a mere three home games.

After third-ranked 10-0 Maryland defeated No. 1 Tennessee in the Sugar Bowl, most felt the Terrapins were college football’s true champs, despite pollsters having awarded the National Championship to the Volunteers before the bowl game. Now being shut out from scheduling fellow SoCons teams the next year, Maryland’s 1952 makeshift schedule was reduced to nine games, instead of eleven as they originally intended. That included a mere three home games.

The Terrapins did not even consider playing SoCon members Washington & Lee, NC State, George Washington, and West Virginia – all schools that had voted in favor of suspending Maryland for going to the Sugar Bowl. Maryland was especially upset with the latter two, programs which they had sponsored to gain membership to the conference.

In the midst of a 15-game unbeaten streak (which would rise to 22), the de facto national champion Terrapins had offers to play dozens of other schools, but no team wanted to play Maryland in College Park. Why schedule an almost assured loss against the mighty Terps?

Riding a huge wave of popularity, Maryland was unable to cash in on its newfound fame. The reigning champion of college football couldn’t find a date to the prom. The limited number of home contests undoubtedly impacted their gate receipts, which helped fund all other sports at the University and left lingering resentment with their SoCon partners.

As dramatic as this seems, it was not unprecedented. Michigan was voted out of the Big Nine for 10 seasons from 1907-16 for failing to follow conference rules. But Maryland and Clemson had merely done as so many other conference teams had done previously by accepting bowl bids before asking for formal permission.

Probation

While on probation in 1952, Maryland streaked out to a 7-0 record and a No. 2 ranking to start the season. Despite being lured by whispers of a bowl bid, this time the Terrapins refused to break Southern Conference rules by participating in one. Maryland did not want to risk probation again and agreed that the rule was now legitimate. Coach Jim Tatum said, “Maryland never has knowingly broken a conference rule.”

While espousing chastity, Maryland was suspected of running around on its conference partners. Rumors swirled that the Terrapins had contacted Michigan State, who was No. 1 in the country for most of 1952, about a potential postseason match-up. Not outright denying the speculation Tatum said, “I see no point in such a game unless both teams end their regular seasons unbeaten.”

Michigan State went on to finish the season undefeated, but Maryland lost its last two games at Mississippi and Alabama (which might have been home games against weaker SoCon teams if not for being on probation). But what if Maryland had gone undefeated? How would the Terrapins’ administration have reacted with another unblemished regular season and the opportunity to play for the National Championship?

To avoid the embarrassing possibility of breaking conference code in the future, there were only two options: Change the rules of the Southern Conference or leave it altogether. Tatum proclaimed, “We do not have any secrets at Maryland. We get into trouble because we tell all we know.” The answer was becoming clear.

At the same time, UNC President Gordon Gray began to reconsider his previous opinion against bowl games and suggested perhaps the matter ought to be left up to individual schools. Maybe the change of heart was in part because UNC had played in three bowl games (twice in the Sugar Bowl and once in the Cotton Bowl) from 1946 to 1949. Going 3-5-2 and 2-8 the next two years while Maryland was riding atop the college football world no doubt left Carolina blue. With boosters eager to see a UNC resurgence, and the difficulties in recruiting in a bowl-prohibited conference, Carolina was to become a secret ally to the Maryland program.

A South Atlantic Conference

Early plans for the 1953 football schedule had Maryland agreeing to SoCon games with only three teams: fellow probation member Clemson, South Carolina – a school that had voted in favor of Maryland going bowling – and UNC. Maryland’s rekindling of relations with UNC may not have been noteworthy at the time, but it would soon pay dividends.

Rumors of a conference split were popping up. In the Atlanta Journal, Harry Mehre, a former coach at Georgia turned sports columnist, predicted that the Southern Conference would break apart by the end of the year. Mehre’s vision for the future had seven to nine schools seceding and joining with the University of Virginia to form a new partnership called “The South Atlantic Conference,” which would be open to bowl games.

West Virginia President Irvin Stewart laughed off the report and said, “It’s all news to me. The gentlemen must have a long grapevine.” Sources close to the SoCon “termed such a move unlikely” as the presidents of UNC, NC State, and Duke already had voted publicly against allowing bowl games so the need to defect was no issue.

Serious talk began when The Washington Post announced Maryland’s Board of Regents would meet in late November 1952 to decide whether the University should remain in the conference. Observant followers of Maryland’s most recent conference exit strategy from the ACC, a cloak and dagger affair that took place in 2012, will note that it was not publicized.

Disgruntled UNC followers, eager for a return to the success of the Charlie “Choo-Choo” Justice days, had been rumored to be offering its coaching position to Tatum, who was a North Carolina alumnus. Another option was UVa’s Art Guepe, who had led Virginia to heights it had not enjoyed since before WWI. It seemed tensions perhaps were brewing just as intensely in Tar Heel country as they were in College Park.

Southern Showdown

At a contentious December league meeting at Clemson, the conference members discussed issues regarding bowl games, financial support to players, and freshman eligibility. There was even talk of dividing the conference into two groups of more closely aligned programs. Reports had surfaced that UVa had been asked to rejoin the conference as a member in a new divisional model.

President Byrd of Maryland publicly approved of creating two divisions within the conference, while George Washington vehemently opposed it. Most felt that the decision would be decided based on the opinions of the “Big Four of North Carolina,” according to the Washington Post.

UNC President Gordon Gray now firmly held the opinion that bowl participation was an issue of “institutional conscience” to be decided by each school separately. Duke, which had hosted the Rose Bowl at the end of the 1941 season over concerns of a Japanese attack on the West Coast and also played in the 1945 Sugar Bowl, had risen as high as fifth in the Associated Press Poll in 1952, boosting talk of its bowl prospects. With two of the Big Four now in favor of bowl games, the tide was perhaps turning. The Washington Post reported, “Many persons claim that Duke and North Carolina usually have their way on conference questions.”

During the conference meeting, and maybe echoing future third-party influences on conference maneuvers (hello ESPN!), two members of the Orange Bowl committee set up a “hospitality room” in the hotel where the gathering was taking place, presumably to help sway the vote on the bowl ban.

Also meeting in a clandestine fashion were Tatum and UNC Athletic Director Chuck Erickson. Both claimed not to have been discussing the coaching vacancy at UNC, which was probably true (Tatum stayed with the Terrapins all the way up to 1956, when he did ultimately accept the job at UNC). But perhaps this meeting was where the true conception of the ACC took place – perhaps in the back seat of Erickson’s car, or more likely in the aforementioned hospitality room.

Calm Before The Storm

By the end of the Southern Conference’s annual meeting, no break-up had occurred. But six months later reports began to circulate that the Big Four were about to break off “and take South Carolina, Clemson, and Maryland with them.” Interestingly, even the northern media invariably seemed to group the Carolina schools in a power group that dragged along the partners of their choice almost by gravitational force.

The reasons for the desired split were the wish for more equal competition (including banning freshman eligibility), lower travel expenses, and a round-robin schedule that would allow for a true champion to be crowned. It was familiar to the refrain chanted in 1921 (birth of the SoCon) and 1932 (creation of the SEC).

After the SEC defections from the Southern Conference in 1932, it’s unknown why the 10 remaining members decided to expand four years later. Seven of the 10 left behind by the SEC teams would form the ACC two decades later. This group basically was the ACC as soon as the SEC schools left. Adding seven more schools to the Southern seems to have just led to another eventual break-up.

The Washington Post revealed that ACC teams were going to sign a deal with the Sugar Bowl wherein their new conference’s football champion would play the winner of the SEC. Both leagues wanted an agreement similar to the Big Ten/Pacific Coast Conference setup in the Rose Bowl. An insider revealed that Sugar Bowl officials told the teams two years prior that if they left the smaller schools behind, the deal was theirs for the taking.

Seeing the conference fall apart around it in 1952, Virginia Tech looked to appease the fracturing group by submitting a proposal for the Southern to finally ban freshman eligibility. And just as quickly an offer to eliminate the bowl ban was made the next day.

The Split

A day after the last ditch effort to salvage the 17-member Southern Conference, the seven aforementioned schools formally left the Southern Conference after eight hours of negotiations. The remaining schools in the conference wished them well.

But the split may not have been officially ratified. Maryland’s Tatum was hedging his bets, “The same old Southern Conference may still be operating next September. Some of the seven don’t have approval of their presidents yet. If even one doesn’t get that approval, I don’t know what would happen. All the plans are being left for a later date.”

GWU Athletic Director, and Southern Conference President, Max Farrington said, “I think some of those schools jumped the gun by not getting approval through. On something as important as this, you would think they would have secured it in advance.”

Maryland President Byrd was on a European trip, the Washington Post proclaimed. But “it was Dr. Byrd who originally conceived the idea of the Southern Conference and it was Byrd who lay the groundwork for the break in the 17-member athletic body this weekend.” Credit or blame, one way or another Maryland was being placed at the center of the break-up of the SIAA in 1921 and now the Southern in 1953.

Herman Blackman of The Washington Post stated, “It’s no secret that other schools in the conference look on Dr. Byrd and Maryland as a Johnny-come-lately combination despite the fact that it was Byrd who got the [ACC] going. Had it not been for Maryland, the seven members which bolted the conference to form their own league would today still be in … unhappy circumstances. It was an uncompromising attitude toward Dr. Byrd and Maryland which prevented the break-up prior to this year. Conference officials didn’t want to be in the position of doing everything Byrd and Maryland wanted. So they waited. Maryland relations with powerful North Carolina proved to be the ideal weapon for Maryland.”

He continued to reveal that UNC’s athletic director visited the Maryland campus working out details for the break-up two weeks prior. Blackman said, “Maryland had the idea, Carolina had the friends.”

Aftermath Of The Southern

The remaining 10 teams in the Southern Conference met in Roanoke to determine their fate. Three schools – Furman, The Citadel, and Davidson – were rumored to be asked to leave the conference due to being too far away from the revised footprint. The Southern was said to be considering moving its basketball tournament to West Virginia after spending years at Reynolds Coliseum in Raleigh. But all were unsure if the Mountaineers would even stay in the league. WVU joined the Southern in 1950 and now three years later it was a crown jewel of what was left of the league.

The remaining 10 teams in the Southern Conference met in Roanoke to determine their fate. Three schools – Furman, The Citadel, and Davidson – were rumored to be asked to leave the conference due to being too far away from the revised footprint. The Southern was said to be considering moving its basketball tournament to West Virginia after spending years at Reynolds Coliseum in Raleigh. But all were unsure if the Mountaineers would even stay in the league. WVU joined the Southern in 1950 and now three years later it was a crown jewel of what was left of the league.

Upon leaving the Southern, Maryland lamented potentially missing out on a newly established rivalry game with Navy. But according to the Washington Post, the Terrapins wanted to “build up a rivalry with the University of Virginia.” Beginning in 1957, the two teams would play one another in their season finale 25 out of the next 35 years, ending a six-decades long tradition of the same kind between UVa and UNC that began in 1892.

The Post article concluded, “Everybody will be happy all around. But the happiest is Maryland and its aggressive president, Dr. Byrd.”

Potential names for the new conference were floated around, including “The Seaboard Conference.” Ultimately, “The Atlantic Coast Conference” was chosen and Wallace Wade, the Commissioner of the Southern, was asked to take the same role with the ACC.

A formal invitation was not made to Virginia, and the school would not genuflect to receive one. UVa had been an independent for 15 seasons and had shown it was not desperate for membership. The seven defectors of the Southern Conference according to the Post, “preferred having Virginia ask them to get in. They [weren’t] planning on extending any formal invitations.”

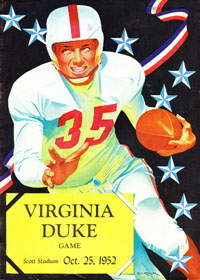

One school that pushed back on offering a bid to Virginia was Duke. Perhaps Duke looked at Virginia as a threat to its dominance on the new league and that bid to the Sugar Bowl. Duke was in the midst of a resurgence with its football program. The Blue Devils won the Southern’s crown in 1952 with a 5-0 conference record. And Virginia was coming off nine consecutive non-losing seasons under Frank Murray followed by Art Guepe, including the program’s first ever top 10 ranking in 1949.

End of Part 2: Up Next, Will the Cavaliers Come Calling?

In the next installment of “Death of a Conference,” the University of Virginia struggles to determine whether or not to enter the new Atlantic Coast Conference. Will it end relations with other schools in state? Will alumni tolerate an association with other schools that may skirt the rules? And will this new conference meet the same fate as the Southern one day?

For more information on the author’s new film Hoos Coming to Dinner: The Virginia Cavaliers Unbelievable Rise to #1, please visit www.UVaFootballHistory.com.